Sally Arai, MD, with her bone marrow transplant patient Ron Gross during a recent checkup.

Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Connects with Donor Halfway Around the World

Sally Arai, MD, with her bone marrow transplant patient Ron Gross during a recent checkup.

Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Connects with Donor Halfway Around the World

When Ron Gross went to his local hospital in Las Vegas in 2011 for routine tests prior to a cervical spine fusion, he had no idea how dramatically his life was about to change. Overnight he went from being a seemingly healthy middle-aged man to a seriously ill patient in need of a bone marrow transplant, then became a transplant survivor with an important new person in his life.

A blood test disclosed abnormalities soon determined to be myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), a cancer of the bone marrow that affects its ability to make healthy blood cells. Gross needed an immediate transfusion of platelets to prepare him for the spinal surgery; soon thereafter he began 10 months of chemotherapy.

Gross talks about his experience in a matter-of-fact way: “At first everything seemed to be working with the chemotherapy, but I was needing supplementary infusions. My blood wasn’t working out too good as far as the counts went. As I progressed, I was averaging two to three transfusions a week of red blood alone and then platelets once or twice a week.”

The Frightening Search for a Bone Marrow Donor

It wasn’t long before his oncologist suggested that he needed to think about finding a donor for a bone marrow transplant. That’s when Gross began to do some research, ultimately deciding to come to Stanford in hopes of having that transplant.

“I was all for the possibility of a transplant from the beginning,” he says. “I was educated very well by the reading material that Stanford provided. They diagrammed what to expect and how successful things have been over the last several years.”

Sally Arai, MD, an associate professor of blood and marrow transplantation, was Gross’s physician. She talks about what kind of patient he was: “He presented for transplant with high-risk disease. What distinguished him was how very optimistic he was. He was just a lovely person from the beginning and very trusting. He started things off by saying, ‘Here I am and I know you can take care of me.’”

Gross started looking for a donor within his family—two sisters and a brother—and, he reports, “the best was eight out of 10 antigens from a sister. But that wasn’t going to be good enough for my condition, so they went to the Be the Match Registry.”

In February, 2014, Gross received his bone marrow transplant from a stranger who was a fully matched, unrelated donor and turned out to be from the other side of the world. His recovery went well, and he reports that he started to feel well about six months later. He had no episodes of rejection.

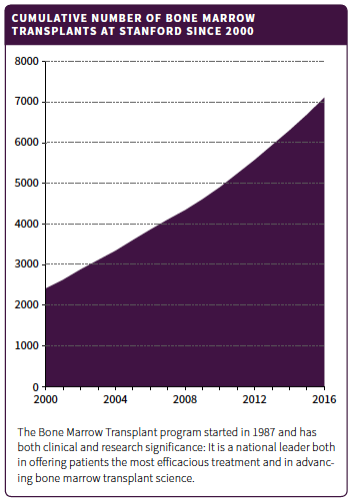

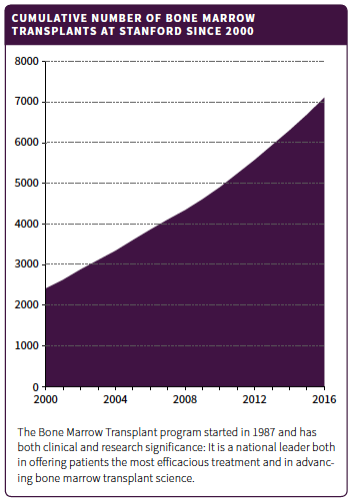

Arai points out how lucky Gross was: “Mr. Gross’s course was pretty smooth in terms of the transplant, just some minor ups and downs, but his overall attitude was just great. Fortunately, he never had to go beyond a fully matched unrelated donor. At the time of his transplant we didn’t have much to offer beyond a fully matched unrelated donor transplant, but that has since changed. For example, cord blood (using stem cells from umbilical cord blood) and haploidentical (partially matched) transplants became other approaches for us and increased our numbers of transplants dramatically.” (See the table.)

When Ron Gross went to his local hospital in Las Vegas in 2011 for routine tests prior to a cervical spine fusion, he had no idea how dramatically his life was about to change. Overnight he went from being a seemingly healthy middle-aged man to a seriously ill patient in need of a bone marrow transplant, then became a transplant survivor with an important new person in his life.

A blood test disclosed abnormalities soon determined to be myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), a cancer of the bone marrow that affects its ability to make healthy blood cells. Gross needed an immediate transfusion of platelets to prepare him for the spinal surgery; soon thereafter he began 10 months of chemotherapy.

Gross talks about his experience in a matter-of-fact way: “At first everything seemed to be working with the chemotherapy, but I was needing supplementary infusions. My blood wasn’t working out too good as far as the counts went. As I progressed, I was averaging two to three transfusions a week of red blood alone and then platelets once or twice a week.”

The Frightening Search for a Bone Marrow Donor

It wasn’t long before his oncologist suggested that he needed to think about finding a donor for a bone marrow transplant. That’s when Gross began to do some research, ultimately deciding to come to Stanford in hopes of having that transplant.

“I was all for the possibility of a transplant from the beginning,” he says. “I was educated very well by the reading material that Stanford provided. They diagrammed what to expect and how successful things have been over the last several years.”

Sally Arai, MD, an associate professor of blood and marrow transplantation, was Gross’s physician. She talks about what kind of patient he was: “He presented for transplant with high-risk disease. What distinguished him was how very optimistic he was. He was just a lovely person from the beginning and very trusting. He started things off by saying, ‘Here I am and I know you can take care of me.’”

Gross started looking for a donor within his family—two sisters and a brother—and, he reports, “the best was eight out of 10 antigens from a sister. But that wasn’t going to be good enough for my condition, so they went to the Be the Match Registry.”

In February, 2014, Gross received his bone marrow transplant from a stranger who was a fully matched, unrelated donor and turned out to be from the other side of the world. His recovery went well, and he reports that he started to feel well about six months later. He had no episodes of rejection.

Arai points out how lucky Gross was: “Mr. Gross’s course was pretty smooth in terms of the transplant, just some minor ups and downs, but his overall attitude was just great. Fortunately, he never had to go beyond a fully matched unrelated donor. At the time of his transplant we didn’t have much to offer beyond a fully matched unrelated donor transplant, but that has since changed. For example, cord blood (using stem cells from umbilical cord blood) and haploidentical (partially matched) transplants became other approaches for us and increased our numbers of transplants dramatically.” (See the table.)

A Two-Year Wait to Meet His Donor

The rules about transplants dictate that donor and recipient cannot learn the identity of one another until, for international transplants, two years have passed. But Gross received many unsigned letters and cards from his donor and responded to them. On the day that he celebrated the second anniversary of his transplant, he dialed the phone number of his donor that he had been given. When the phone rang busy he hung up to try again in a few minutes, and his own phone immediately rang. His donor’s number was busy because she was dialing his number.

Karolina Wierciak lives in Szczecin, Poland. She signed up to be an organ donor in honor of a cousin who had lost his life to throat cancer. Because the rules in Poland reserve all donated organs for Polish citizens, she chose to enroll in a registry in Germany, making it possible for anyone in the world to receive her donation if she was a match.

Donor and recipient quickly found how alike they are, down to having birthdays two days apart. Recently Gross traveled to Poland and spent time with Wierciak, cementing their strong friendship. They are in touch via email and Facebook, and they text daily even now. As Gross says, “Even though she is the CEO of her company, working long hours, she decided to drive 211 miles to Germany and donate her bone marrow for international distribution, a decision that saved my life.”

The Field Continues to Evolve

Arai talks about the changes over just the last several years for patients with blood cancers. “For certain diseases, there have been recent exciting advancements like CAR-T cell therapy. That therapy is open to certain diseases like lymphomas and leukemias. But MDS, which was Ron’s diagnosis, is still treated with chemotherapeutic agents from many years back. Ultimately for a cure for these patients, it has to be a transplant.”

Patient characteristics have also changed to favor patients who were once considered too old to undergo transplant. “It used to be that transplants were for younger people who could handle the toxicity,” says Arai, “but now we have reduced-intensity transplants. Ron represents older patients, and they have become the norm for us. The average age is now in the 60s.”

So, Ron Gross was lucky on several levels. Perhaps the most important piece of luck to him was the opportunity to form his close relationship with Wierciak. Asked how he would introduce Wierciak to a friend, he says, “I would introduce her as my sister Karolina and my hero.”

The number of bone marrow transplants at Stanford, 2000–2016. The program started in 1987 and has both clinical and research significance: It is a national leader both in offering patients the most efficacious treatment and in advancing bone marrow transplant science.

A Two-Year Wait to Meet His Donor

The rules about transplants dictate that donor and recipient cannot learn the identity of one another until, for international transplants, two years have passed. But Gross received many unsigned letters and cards from his donor and responded to them. On the day that he celebrated the second anniversary of his transplant, he dialed the phone number of his donor that he had been given. When the phone rang busy he hung up to try again in a few minutes, and his own phone immediately rang. His donor’s number was busy because she was dialing his number.

Karolina Wierciak lives in Szczecin, Poland. She signed up to be an organ donor in honor of a cousin who had lost his life to throat cancer. Because the rules in Poland reserve all donated organs for Polish citizens, she chose to enroll in a registry in Germany, making it possible for anyone in the world to receive her donation if she was a match.

Donor and recipient quickly found how alike they are, down to having birthdays two days apart. Recently Gross traveled to Poland and spent time with Wierciak, cementing their strong friendship. They are in touch via email and Facebook, and they text daily even now. As Gross says, “Even though she is the CEO of her company, working long hours, she decided to drive 211 miles to Germany and donate her bone marrow for international distribution, a decision that saved my life.”

The Field Continues to Evolve

Arai talks about the changes over just the last several years for patients with blood cancers. “For certain diseases, there have been recent exciting advancements like CAR-T cell therapy. That therapy is open to certain diseases like lymphomas and leukemias. But MDS, which was Ron’s diagnosis, is still treated with chemotherapeutic agents from many years back. Ultimately for a cure for these patients, it has to be a transplant.”

Patient characteristics have also changed to favor patients who were once considered too old to undergo transplant. “It used to be that transplants were for younger people who could handle the toxicity,” says Arai, “but now we have reduced-intensity transplants. Ron represents older patients, and they have become the norm for us. The average age is now in the 60s.”

So, Ron Gross was lucky on several levels. Perhaps the most important piece of luck to him was the opportunity to form his close relationship with Wierciak. Asked how he would introduce Wierciak to a friend, he says, “I would introduce her as my sister Karolina and my hero.”

The number of bone marrow transplants at Stanford, 2000–2016. The program started in 1987 and has both clinical and research significance: It is a national leader both in offering patients the most efficacious treatment and in advancing bone marrow transplant science.