Caring for COVID-19 Patients:

Department of Medicine Comes

Together to Serve Community

Impacted by COVID-19

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, through two surges, and now during a “new normal,” one thing has never changed: The Stanford Department of Medicine staff and faculty have provided the best care possible to their patients, offering hope during a dark time.

Doctors, trainees, and staff held patients’ hands, arranged Zoom calls to family members, and performed clinical trials to find drugs to treat the virus.

Dedicated members from the infectious diseases, pulmonary and critical care medicine, and hospital medicine groups worked together to provide inpatient care for their COVID-19 patients, bolstered by Department of Medicine leadership and volunteers from other divisions and departments.

They found meaning in providing this necessary care and are proud to have come together to serve their community during this unprecedented time.

Infectious Disease at the Forefront

When the novel coronavirus started spreading within and beyond China in early 2020, people throughout Stanford Medicine began making plans for handling infected patients. According to laboratory tests, COVID-19 patients began showing up at Stanford clinics in late February and early March. By mid-March, elective surgeries were put on hold, visitors were temporarily barred, and medical students paused their clinical rotations. A few days later, the governor of California announced a statewide lockdown.

When COVID-19 patients arrived, infectious disease (ID) doctors were ready. They created a consult service specifically for COVID-19 patients at the Stanford Hospital. “We were very much at the forefront of providing care from the very beginning at Stanford,” says Upinder Singh, MD, professor and division chief of infectious diseases. “Even early in the pandemic, we were comfortable with infection control practices, and we have experience seeing patients with new emerging infections.”

Early on, with so little known about the virus, there was much anxiety about how it spread, how to protect patients and staff, and the best way to treat the infection. No one knew the right time to intubate a struggling patient or which drugs could be repurposed for treatment.

In that first month, new study results appeared daily, sometimes with conflicting results. Shanthi Kappagoda, MD, clinical associate professor of infectious diseases, sorted through the information to develop clinical care, education, and treatment guidelines, in concert with colleagues in hospital medicine and pulmonary and critical care medicine.

“When we saw our first hospitalized COVID-19 patients at Stanford, there were almost no clinical trial data on how to treat COVID-19 and no national guidelines,” says Kappagoda. “At the same time, there was a flood of anecdotal information from colleagues in Seattle, Boston, and New York, which changed from day to day.”

Kappagoda and David Ha, PharmD, infectious diseases pharmacist, worked with a committee of clinicians to develop evidence-based treatment guidelines and present them in a simple, easy-to-disseminate format.

“We are fortunate in the ID division to have a deep bench of virologists, immunologists, and data scientists who helped us assess the early data—in vitro, preclinical, and clinical—and sift out what could help us improve our care and what experimental therapies were likely to cause harm,” says Kappagoda. “As chair of the ID COVID-19 treatment guidelines committee, I am proud of how our division stepped up to support the Department of Medicine.”

Infection Control

Another key role of the ID division is keeping patients and staff safe through infection control. Lucy Tompkins, MD, PhD, Lucy Becker, professor of medicine and microbiology and immunology, and the hospital epidemiologist for Stanford Health Care, has carried the enormous burden of halting the spread of infections within the hospital, including COVID-19. “It’s been a nonstop job,” she says—the hardest of her 38 years at Stanford.

Along with a team of nine infection preventionists, including Sasha Madison, administrative director of infection prevention and control at Stanford Health Care, Tompkins decides, implements, and enforces infection control policies, covering correct testing and quarantine protocols and the use of proper personal protective equipment (PPE) for each medical procedure.

“The infection control group was dealing with changing guidelines that were morphing on a daily basis,” says Marisa Holubar, MD, clinical associate professor of infectious diseases, who was also involved in infection control efforts. She says it was challenging to take in and communicate that information effectively to the thousands of staff members at the hospital and clinics. “Our efforts really minimized the exposure of health care workers to COVID-19 in the hospital. We armed them with information so they could protect themselves.”

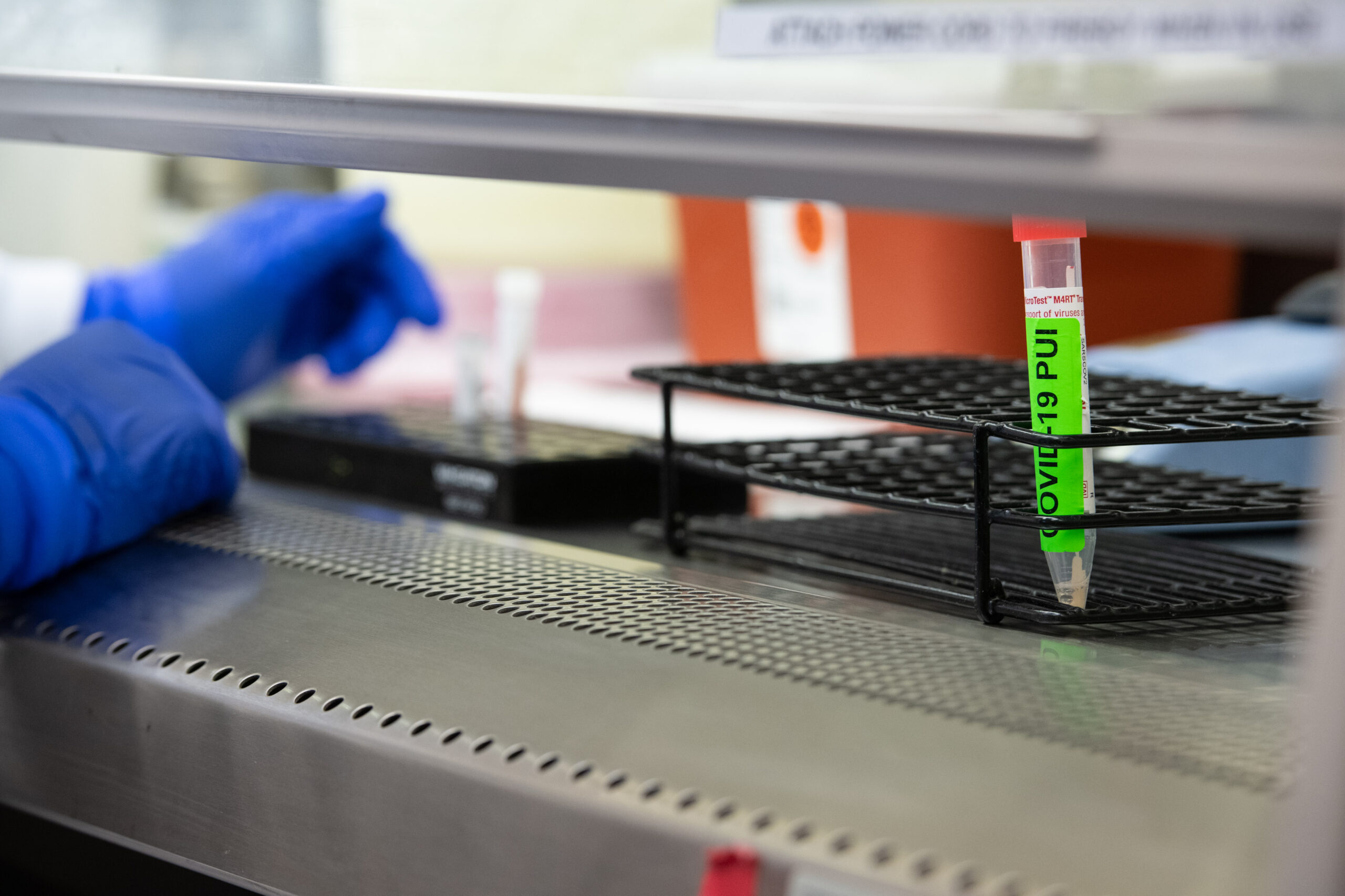

A swab awaits testing for COVID-19 in the Clinical Virology Laboratory

Benjamin Pinsky, MD, PhD

Stanford Hospital and the clinics were fortunate to have adequate PPE supplies throughout the pandemic to keep staff and patients safe. The single occupancy rooms at the new hospital helped with patient isolation.

Tompkins oversees contact tracing within the hospital in the event of an outbreak. Only once was there an exposure event where a patient infected staff members—resulting from a false negative COVID-19 test at another facility. She reviews each hospitalized COVID-19 patient’s chart to determine when the person can leave isolation, using a diagnostic test developed by Benjamin Pinsky, MD, PhD, associate professor of pathology and infectious diseases, and medical director of the Clinical Virology Laboratory for Stanford Health Care.

Family visitation falls under Tompkins’ purview. She has been instrumental in enacting protocols for safe visitation, which resumed in March 2021. “I think that is the only humane thing to do, especially for patients who are truly ill and when they’re going to be in the hospital for any length of time,” says Tompkins.

Making Progress through Clinical Trials

ID faculty began enrolling patients in clinical trials early on—the first on March 14, 2020. Aruna Subramanian, MD, clinical professor of infectious diseases, and Philip Grant, MD, assistant professor of infectious diseases, participated in trials for remdesivir, which is now the backbone of patient treatment. They were involved in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV-1) trial, which evaluated several immune modulators for their ability to tamp down an overactive immune response in COVID-19 patients. They collaborated with hospital medicine and pulmonary, allergy, and critical care medicine teams. Grant led the Johnson & Johnson vaccine trial at Stanford.

“It’s unbelievably gratifying to be involved in trials that were effective,” says Subramanian. “Patients were so interested in getting treatment, you could see the gratitude on their faces.”

With support from the Dean’s Office, Catherine Blish, MD, PhD, professor of infectious diseases, set up a state-of-the-art biosafety level 3 lab space so that researchers could safely study cultures of the virus—an improvement over their previous smaller space.

“There was just an amazing amount of work they did behind the scenes,” says Subramanian. “I feel like the entire ID group was involved in so many aspects of COVID-19, not always known to the world.”

Hospital medicine faculty members also participated in clinical trials from the earliest days of the pandemic, under the leadership of Neera Ahuja, MD, clinical professor of medicine, and Kari Nadeau, MD, PhD, Naddisy Foundation Professor of Pediatric Food Allergy, Immunology and Asthma.

At Stanford Hospital, Nidhi Rohatgi, MD, clinical associate professor of hospital medicine; Jessie Kittle, MD, clinical assistant professor of hospital medicine; Andre Kumar, MD, MEd, clinical assistant professor of hospital medicine; Rita Pandya, MD, clinical assistant professor of hospital medicine; and Jeffrey Chi, MD, clinical associate professor of hospital medicine, participated in the NIH Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT) that led to the approval of remdesivir and the granting of emergency use authorization for the anti-inflammatory drug baricitinib. This clinical trial was the first ever conducted at ValleyCare, Stanford Health Care’s sister hospital located in the East Bay’s Tri-Valley region, through the efforts of Evelyn Bin Ling, MD, clinical assistant professor of hospital medicine; Minjoung Go, MD, clinical assistant professor of hospital medicine; and David Svec, MD, MBA, clinical associate professor of hospital medicine. “When COVID-19 hit in March, we had a sense of urgency to bring more COVID-19-related studies to the university and to ValleyCare, and to make that available for patients,” says Ling.

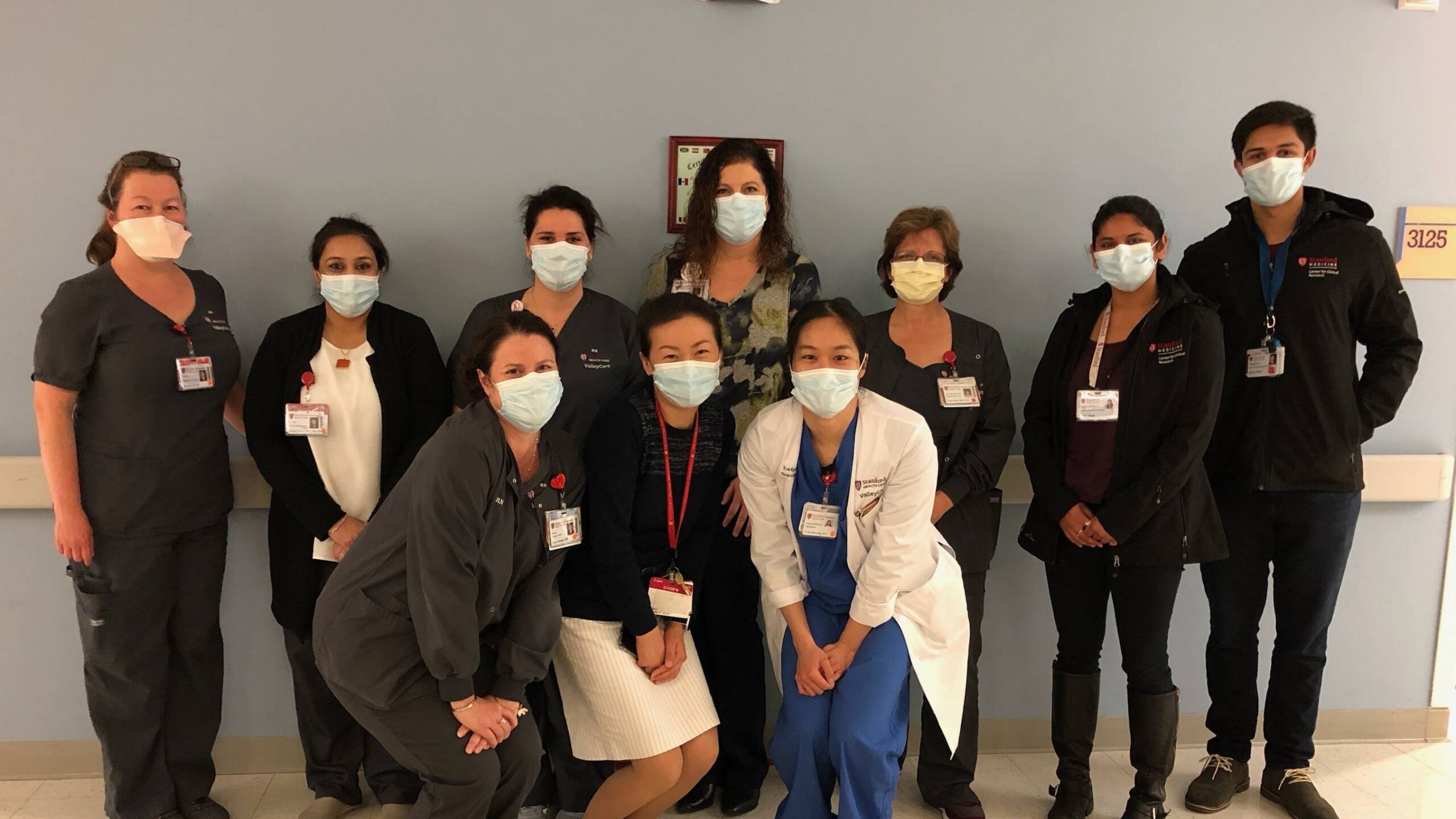

This clinical trial was the first ever conducted at Stanford ValleyCare

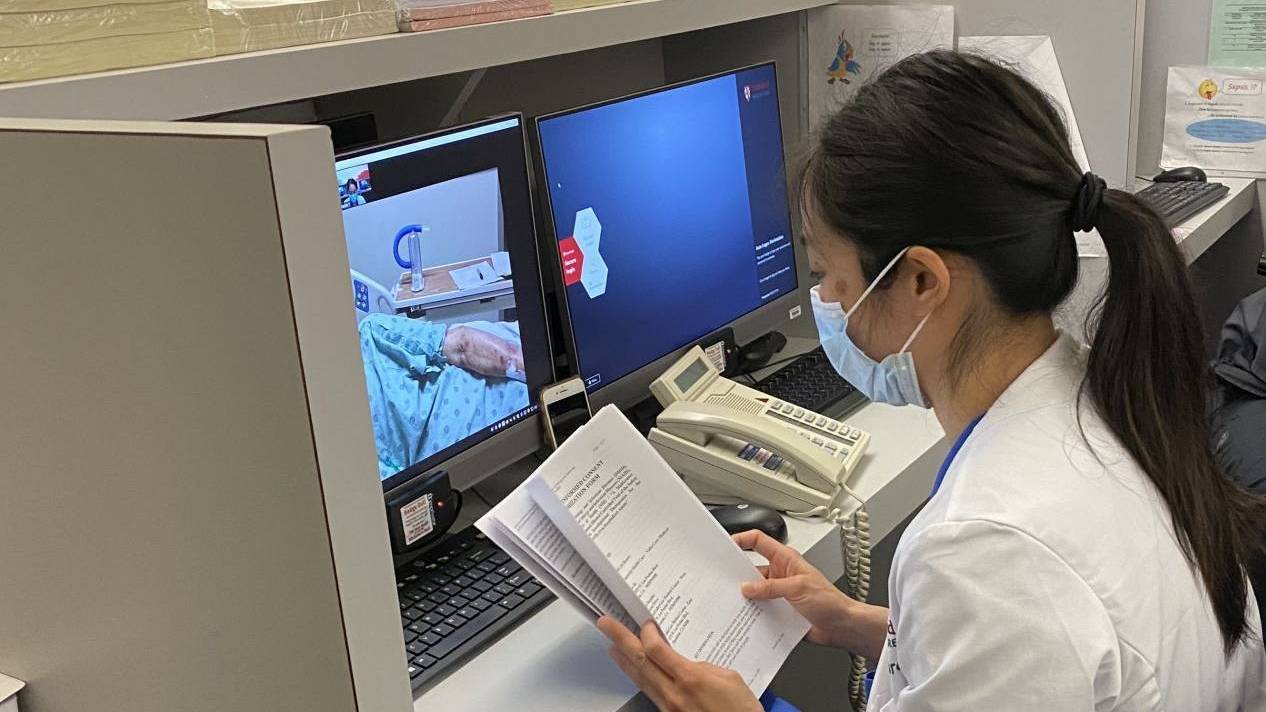

Minjoung Go, MD reviews procedures

Stanford ValleyCare faculty and staff on the first day of clinical trial enrollment

The Winter Surge

As in many parts of the country, COVID-19 cases ramped up quickly in mid-November. At the peak of the surge, the general wards held more than 100 patients, about half of them with COVID-19. Chi organized faculty to staff the surge teams. “People were going two weeks, or in some cases even three weeks, straight without a day off,” he says.

“Seeing that spirit of camaraderie, and the willingness to serve, was just heartwarming for me,” says Ahuja. “Some of my faculty are young and have small children at home. Some were actually pregnant themselves, and they never said no. They just showed up time and time again, ready to serve our patients.”

Other divisions loaned their faculty to staff the surge teams, adding to the spirit of collaboration.

Ultimately, about 20% of patients from the general COVID-19 wards were transferred to the ICU, but some returned and recovered. Overall, the COVID-19 mortality rate at Stanford Hospital reached just 6%, far lower than the average U.S. in-hospital mortality rate of 13.6%.

The sacrifices of the hospitalists were perhaps most acute during the holiday season. Physicians often work holidays, but staff couldn’t even gather at work to celebrate during the pandemic. Many faculty and staff decided to isolate from their families for fear of bringing the virus home.

Poonam Hosamani, MD, clinical associate professor of medicine, was not yet vaccinated during the winter surge, so she sent her husband and 4-year-old daughter to live with her elderly parents. She celebrated Christmas and New Year’s with her family over Zoom.

Of course, the holidays were more difficult for the patients. Hosamani was shocked by how many patients had multiple relatives also hospitalized due to COVID-19.

Angela Rogers, MD (left), reviews treatment guidelines for patients with COVID-19 with a colleague

Small Victories

There were some bright spots in the ICU during the pandemic. While many critical care patients never leave the ICU, large numbers of COVID-19 patients recovered. Staff rang bells and cheered as long-term patients were wheeled off to rehab.

“Seeing people get better in the ICU was really encouraging and really something that made me interested in doing pulmonary and critical care,” says Kyle Fahey, MD, a resident who gave up two of his rotations to volunteer in the ICU. “There was a really strong sense of camaraderie in the COVID-19 ICU. I think that was a big part of what made it so bearable, even given the difficult circumstances.”

Carrie Cao, MD, a second-year resident, initially had selected a different specialty, but her time volunteering in the COVID-19 ICU ward crystallized her interest in pulmonary medicine and critical care, and she has now switched her focus

“Every COVID extubation was really emotional,” says Cao. “It felt like a victory.”

Despite the utter exhaustion that many physicians have felt after caring for COVID-19 patients in the last year, Rogers and others said that it was an honor to serve their community and it brought them a deep sense of fulfillment.

“I’ll have this experience for the rest of my life as I take care of people,” says Thomas. “Overall, it’s confirmed that this is where I’m meant to be.”

Chief residents Andrew Moore, MD (left), and Mita Hoppenfeld, MD (right), organized residents to staff the surge teams during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic