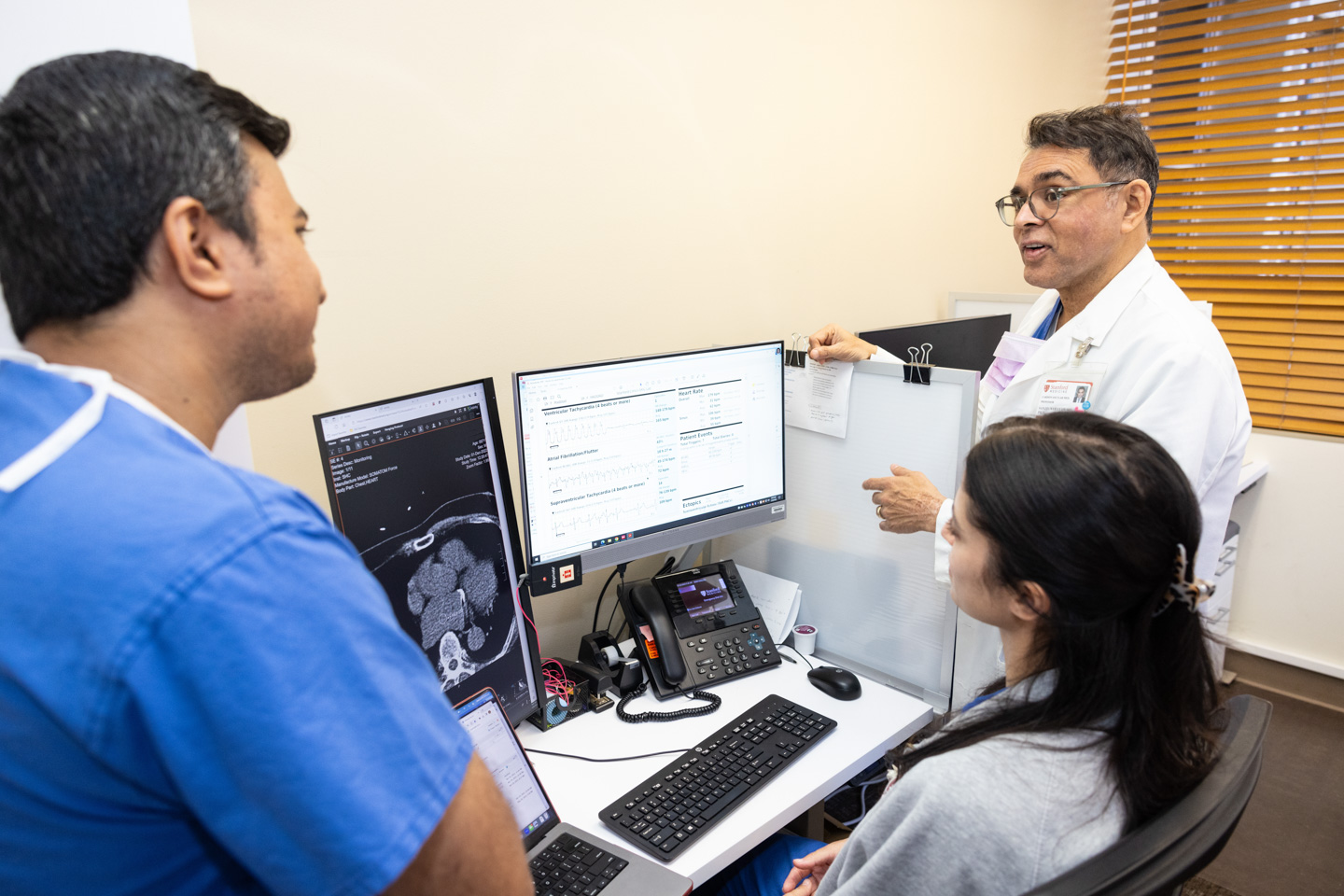

From left: Desiree Steinberg, NP; Prasanth Ganesan, PhD; and Sanjiv M. Narayan, MD, PhD

CHIP: Where Artificial Intelligence and Cardiology Come Together

From left: Desiree Steinberg, NP; Prasanth Ganesan, PhD; and Sanjiv M. Narayan, MD, PhD

CHIP: Where Artificial Intelligence and Cardiology Come Together

“Computer tools are everywhere. They’re in your phone. They’re in your TV remote. They’re in your car gearbox,” says Sanjiv M. Narayan, MD, PhD, professor of cardiovascular medicine. As the benefits of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning in the medical setting become increasingly clear, it is imperative that physicians understand them, so they can be safely and thoughtfully leveraged to improve research and patient care. That is why he and his co-director Alison Marsden, PhD, have founded the first-of-its-kind Computational Medicine in the Heart: Integrated Training Program (CHIP). Marsden is Douglass M. and Nola Leishman Professor of Cardiovascular Diseases in the departments of Pediatrics, Bioengineering, and, by courtesy, Mechanical Engineering.

“If we don’t understand [machine learning and AI], we are ceding our responsibility to tech companies, who may have priorities other than patient care or science,” Narayan says. “If we understand these things better, we are better prepared. … It just makes the scientific mission better.”

At the same time, computer scientists and engineers, the professionals who typically develop the computer-based technologies that are used in medicine, may do a better job if they understand the nuanced medical and biological contexts in which they are used.

Learning How to Speak the Same Language

Welcoming its very first students during the summer of 2023, CHIP operates under the aegis of the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute (CVI) and the Institute for Computational and Mathematical Engineering (ICME). It is a truly multidisciplinary program, accepting students with diverse backgrounds to develop the novel specialty of computational medicine. CHIP cross-trains biologists and medical specialists on the one hand and engineers, mathematicians, and computer scientists on the other. “The idea is to have enough [mutual] understanding so we can talk the same language,” says Narayan, who in addition to being director of CHIP is also a professor of medicine and co-director of another multidisciplinary program — the Stanford Center for Arrhythmia Research.

While many are already working in the space that CHIP straddles, most are formally educated in one field and self-taught in the other. CHIP provides education that spans both while at the same time offering opportunities to make practical use of this multidisciplinary training in clinical and research settings.

Made possible via a prestigious and highly sought-after National Institutes of Health (NIH) T32 grant, the two-year research program offers on-the-job practical training to those with an MD or PhD in the fields of medicine, biology, computer science, or engineering. Students engage with Stanford faculty across the entire campus, including the schools of Medicine, Engineering, and Humanities and Sciences. “We want people who are committed to this intersection,” says Narayan. “They have proven to us that they are not just doing it to work with a certain faculty. They believe in the mission. To me, it’s a mindset.”

Harnessing a Powerful Tool in Medicine

“Medical AI, when it is used to complement the physician, is incredibly powerful,” continues Narayan. Examples include the Apple Watch, which can detect atrial fibrillation, or AI and machine learning algorithms to aid in the interpretation of findings on imaging. Unlike people, AI doesn’t get tired. It doesn’t get hungry. It doesn’t have good and bad days. But computers should never replace a physician. They simply provide new pieces of information with which to make decisions. In fact, a recent Stanford study revealed that using machine learning can help identify evidence of cardiovascular disease on imaging that was missed by clinicians. One of Narayan’s own specialties is in digital phenotyping to predict cardiovascular outcomes. The use of AI and machine learning allows for the number of factors included in an individual digital phenotype to be virtually limitless.

CHIP program participants from left: Prasanth Ganesan, PhD, cardiovascular medicine postdoctoral fellow; Desiree Steinberg, NP; and Sanjiv M. Narayan, MD, PhD

“Computer tools are everywhere. They’re in your phone. They’re in your TV remote. They’re in your car gearbox,” says Sanjiv M. Narayan, MD, PhD, professor of cardiovascular medicine. As the benefits of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning in the medical setting become increasingly clear, it is imperative that physicians understand them, so they can be safely and thoughtfully leveraged to improve research and patient care. That is why he and his co-director Alison Marsden, PhD, have founded the first-of-its-kind Computational Medicine in the Heart: Integrated Training Program (CHIP). Marsden is Douglass M. and Nola Leishman Professor of Cardiovascular Diseases in the departments of Pediatrics, Bioengineering, and, by courtesy, Mechanical Engineering.

“If we don’t understand [machine learning and AI], we are ceding our responsibility to tech companies, who may have priorities other than patient care or science,” Narayan says. “If we understand these things better, we are better prepared. … It just makes the scientific mission better.” At the same time, computer scientists and engineers, the professionals who typically develop the computer-based technologies that are used in medicine, may do a better job if they understand the nuanced medical and biological contexts in which they are used.

Learning How to Speak the Same Language

Welcoming its very first students during the summer of 2023, CHIP operates under the aegis of the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute (CVI) and the Institute for Computational and Mathematical Engineering (ICME). It is a truly multidisciplinary program, accepting students with diverse backgrounds to develop the novel specialty of computational medicine. CHIP cross-trains biologists and medical specialists on the one hand and engineers, mathematicians, and computer scientists on the other. “The idea is to have enough [mutual] understanding so we can talk the same language,” says Narayan, who in addition to being director of CHIP is also a professor of medicine and co-director of another multidisciplinary program — the Stanford Center for Arrhythmia Research. While many are already working in the space that CHIP straddles, most are formally educated in one field and self-taught in the other. CHIP provides education that spans both while at the same time offering opportunities to make practical use of this multidisciplinary training in clinical and research settings.

Made possible via a prestigious and highly sought-after National Institutes of Health (NIH) T32 grant, the two-year research program offers on-the-job practical training to those with an MD or PhD in the fields of medicine, biology, computer science, or engineering. Students engage with Stanford faculty across the entire campus, including the schools of Medicine, Engineering, and Humanities and Sciences. “We want people who are committed to this intersection,” says Narayan. “They have proven to us that they are not just doing it to work with a certain faculty. They believe in the mission. To me, it’s a mindset.”

Harnessing a Powerful Tool in Medicine

“Medical AI, when it is used to complement the physician, is incredibly powerful,” continues Narayan. Examples include the Apple Watch, which can detect atrial fibrillation, or AI and machine learning algorithms to aid in the interpretation of findings on imaging. Unlike people, AI doesn’t get tired. It doesn’t get hungry. It doesn’t have good and bad days. But computers should never replace a physician. They simply provide new pieces of information with which to make decisions. In fact, a recent Stanford study revealed that using machine learning can help identify evidence of cardiovascular disease on imaging that was missed by clinicians. One of Narayan’s own specialties is in digital phenotyping to predict cardiovascular outcomes. The use of AI and machine learning allows for the number of factors included in an individual digital phenotype to be virtually limitless.

CHIP program participants from left: Prasanth Ganesan, PhD, cardiovascular medicine postdoctoral fellow; Desiree Steinberg, NP; and Sanjiv M. Narayan, MD, PhD

We are at the cutting edge of next-generation computational engineering and medicine, to deliver solutions to improve the lives of patients.

— Sanjiv Narayan, MD

Integrating New Technology by Improving Competence Across Disciplines

Narayan uses the analogy of the increasing importance of statistics in medicine to explain the importance of programs like CHIP. “There was a time when physicians were not taught statistics. Now it’s such a major part of what we [as physicians] do,” he says. Computer science is becoming integral to how medicine is practiced, just as statistics has become integral to weighing evidence and ultimately making clinical decisions.

Narayan expects that by the end of their training, students will have worked and published across disciplines. Upon graduation, they will continue to leverage their understanding of computational medicine in their careers in academia, government, or industry. “The quality of our graduates will make this a signature for Stanford,” he says. “We are at the cutting edge of next-generation computational engineering and medicine, to deliver solutions to improve the lives of patients.” Ultimately, he says, he would like CHIP to be the catalyst behind the birth of the field of computational medicine, with one day perhaps a Center for Computational Medicine within the Stanford School of Medicine. “If we have done that,” he says, “we have moved the needle. The science will be more robust, outcomes should be better. Patients should get better treatment.”