COVID-19 Modeling Team at Forefront of Pandemic Projections and Planning

COVID-19 Modeling Team at Forefront of Pandemic Projections and Planning

Just weeks after the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a global pandemic in March 2020, a team of Stanford Health Policy faculty and researchers scrambled to launch a modeling framework to investigate the epidemiology of COVID-19 and to evaluate policy responses.

A year later, the Stanford-CIDE Coronavirus Simulation Model (SC-COSMO) remains at the forefront of dozens of projection models in the United States and Mexico, while helping the state of California and its prison system, hospitals, and health care providers plan for and mitigate the impact of the pandemic. As of May 2021, the SC-COSMO team’s work has resulted in a half dozen studies published in medical journals and open data sites.

“The pandemic has continued to evolve, as have the policy questions and available interventions,” says Jeremy Goldhaber-Fiebert, PhD, associate professor of medicine at Stanford Health Policy (SHP). “Basic questions about how quickly the virus would spread in diverse populations were followed by urgent planning for hospital capacity during the surges and then nonpharmaceutical interventions and social distancing questions.”

Jeremy Goldhaber-Fiebert, PhD

Jason Andrews, MD

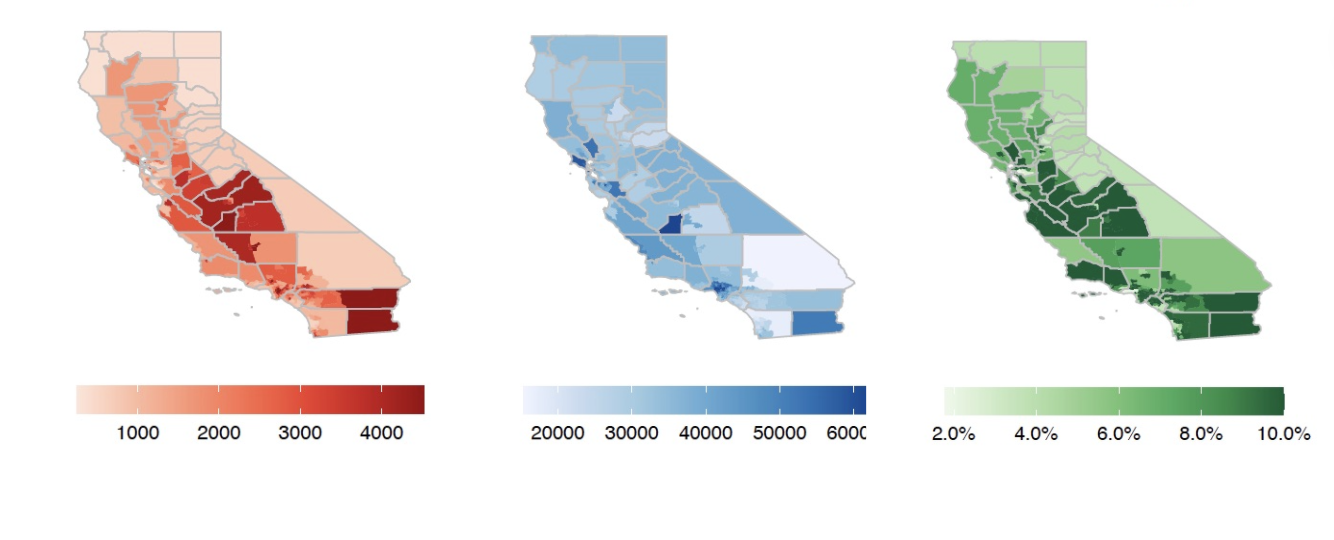

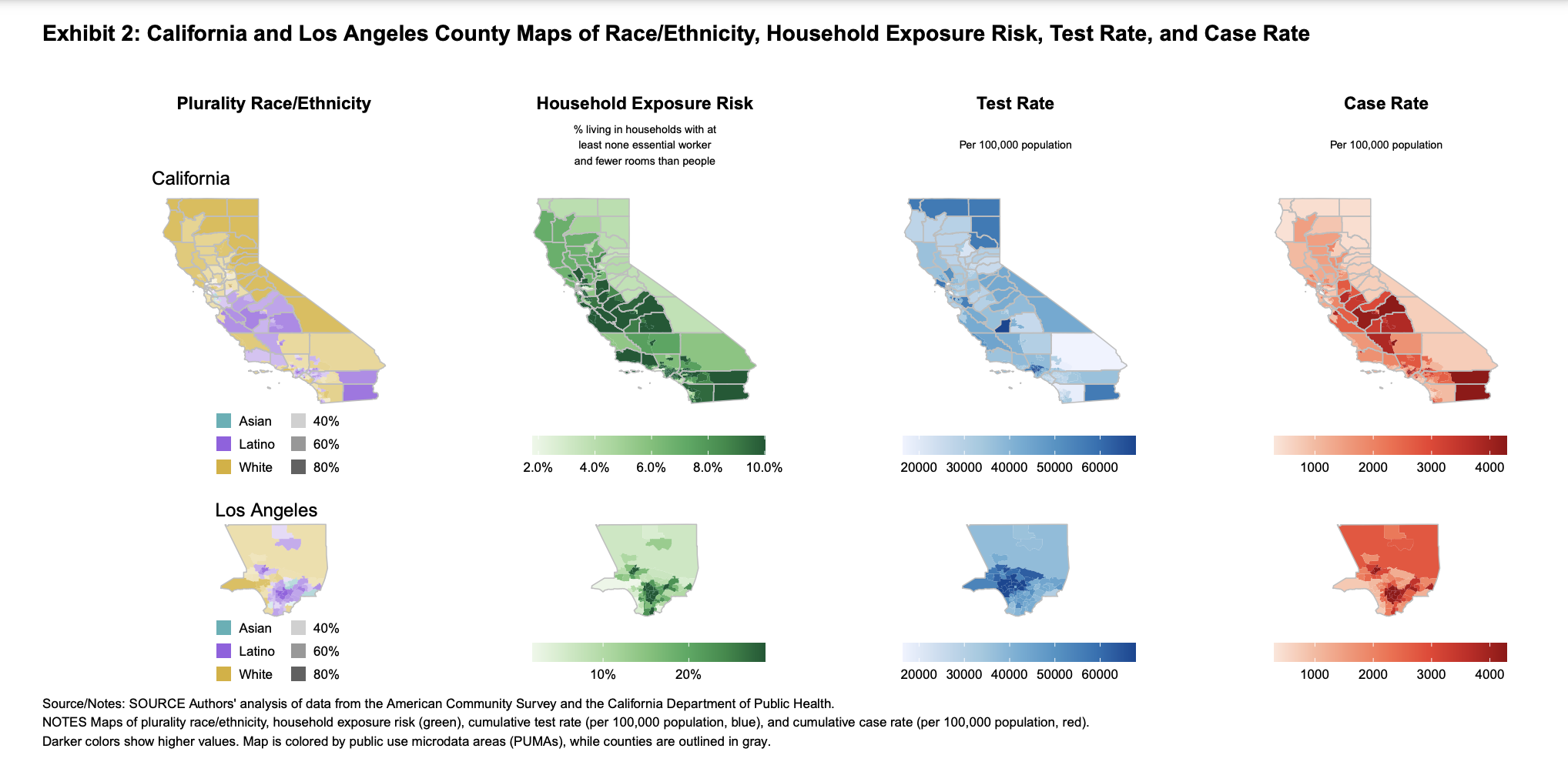

Latino populations throughout California have higher average levels of exposure risk due to occupation and housing characteristics. Areas with high exposure risk tend to have higher case rates but below average testing rates

“We are motivated because timely and rigorous

science can be used to protect people’s health

and well-being, especially those who are often

neglected or are at greatest risk”

“We are motivated because timely and rigorous

science can be used to protect people’s health

and well-being, especially those who are often

neglected or are at greatest risk”

Stanford Student Collaborations

——————–

Marissa Reitsma

Anneke Claypool

The SC-COSMO project has allowed Stanford students to use the modeling and data analytic tools to shed light on important questions about the pandemic.

Marissa Reitsma, a PhD candidate in health policy, for example, used five years of the American Community Survey of the Census Bureau to map out areas with a high proportion of people at increased risk of being exposed to COVID-19 due to their occupation and housing characteristics. She and her colleagues published their findings in the Journal of General Internal Medicine. Their study found that communities of color may be most susceptible to low vaccine coverage due to long-standing disparities in health care, mistrust fueled by a history of exploitation in clinical trials, and other structural risk factors.

“This study provides hard numbers to what has been acknowledged in public discourse,” Reitsma says. “We hope our study motivates equity-focused policies like support for safe self-isolation, cash assistance, and paid sick leave for low-income individuals that need to quarantine.”

Reitsma also worked with Anneke Claypool, a PhD candidate in management science and engineering, focusing on the fact that Black and Hispanic populations are being hit harder than most by the pandemic due to a variety of socioeconomic and economic reasons. The two students won an early-career grant from the Stanford Center for Population Health Sciences to analyze multiple streams of data, which they are using to evaluate the effects of different interventions and policies in order to identify the most important drivers of racial disparities. They believe their results will help decision makers prioritize effective interventions. Their work has been focused on approaches to vaccine access and acceptance to improve population health.