Being done with treatment allows Kristy Kerivan to focus on the things that really matter.

From Oncology Staff to Oncology Patient

Being done with treatment allows Kristy Kerivan to focus on the things that really matter.

From Oncology Staff to Oncology Patient

Kristy Kerivan thought her fatigue was from a cardiac issue and was not expecting her diagnosis: breast cancer that was HER2+, one of the more aggressive types. As senior administrative division director in the Department of Medicine’s division of oncology, she fortunately had immediate access to resources.

“I was panicked,” Kerivan says about her diagnosis. “The first person I went to was Heather Wakelee, MD, chief of oncology and also one of my bosses, and we talked through what I was facing. After that, it was a whirlwind.”

While Kerivan’s mom had previously been treated for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a noninvasive early form of breast cancer, Kerivan’s cancer had spread into breast tissue, making treatment lengthier and more complex.

And that treatment lasted a full year, starting with chemotherapy followed by lumpectomy surgery, radiation, and Herceptin, an IV medication that targets HER2+ receptors to stop cancer cell growth. Says Kerivan, “I feel fortunate that the cancer was caught early and that I had access to this medication because without it my prognosis would have been very different.”

Cancer Care at Stanford

Kerivan likes to tell people that if you’re going to get cancer, you might as well get it while working in the division of oncology at a major academic institution like Stanford. “The care I received at Stanford was exceptional,” she says, referring to her 100-plus visits to Stanford during her yearlong course of treatment.

Kerivan has been in her current position since August 2020 and had worked as administrative director for Stanford’s Vera Moulton Wall Center for Pulmonary Vascular Disease for 17 years. Extremely familiar with the administrative side of health care, Kerivan found being a patient to be an eye-opening experience. “I was surprised about the things I didn’t know,” she explains. “While I understood how specialized cancer treatment is, I didn’t know just how complex cancer care is or how treatment impacts every area of your body.”

As a patient, she found it reassuring to visit areas she knew in passing as a staff person. “Because I was familiar with the hospital, it didn’t feel like a big, intimidating medical facility,” she says.

“And from the people who checked me in, to the radiation therapists and the nurses who administered chemo — all of my personal interactions made me feel like people cared.”

As a comprehensive care center, Stanford offers an extensive array of cancer specialists. Allison Kurian, MD, professor of oncology and of epidemiology and population health at the Stanford School of Medicine, served as Kerivan’s breast oncologist and treatment physician, and her care team included a breast surgeon, a dermatology oncologist, a radiation oncologist, and a neuro-oncologist. Kerivan received periodic calls from a social worker and outreach specialist who helped her manage the emotional and nonmedical aspects of treatment.

“I felt lucky to have access to a wealth of specialists and support services that might not have been available to me at other institutions. I also felt a deeper appreciation for all the work conducted by Stanford researchers to find cures for cancer and other diseases. I like to think that, in some small way, I supported that progress,” she says.

From the people who checked me in, to the radiation therapists and the nurses who administered chemo — all of my personal interactions made me feel like people cared.

Going the Extra Mile

An example of the exceptional care and support Kerivan received occurred one Easter Sunday while she was experiencing side effects from chemotherapy. Wanting to avoid going to the emergency room and possibly exposing herself to COVID-19 and other germs when her resistance was weakened, she was relieved to learn that the Infusion Center was open every day of the year. A nurse practitioner was able to see her that day and helped address her symptoms.

Kerivan took a medical leave at the beginning of her treatment, then worked a reduced 10-hours-per-week schedule from April to October 2022. This allowed her return to full-time work to be less of a shock, and it gave her ongoing support from colleagues, especially from her administrative and finance team. “I’ll never forget the many offers of help and messages of support from staff and faculty throughout this process,” she notes. Among the small acts of kindness were the groceries that Bhuvana Ramachandran, administrative division director in the division of hematology, bought and delivered to her. Kerivan’s bosses, Wakelee and Cathy Garzio, director of finance and administration for the Department of Medicine, were also extremely supportive while she returned to full health. “Cathy checked on me frequently to see how I was doing and sent me flowers and food via DoorDash,” recalls Kerivan. “Heather was a great medical resource for questions, and she made sure I was taking care of myself and not working too much. A big part of their support was what they didn’t do — they never made me feel pressured about work, and they let me do what I felt capable of.”

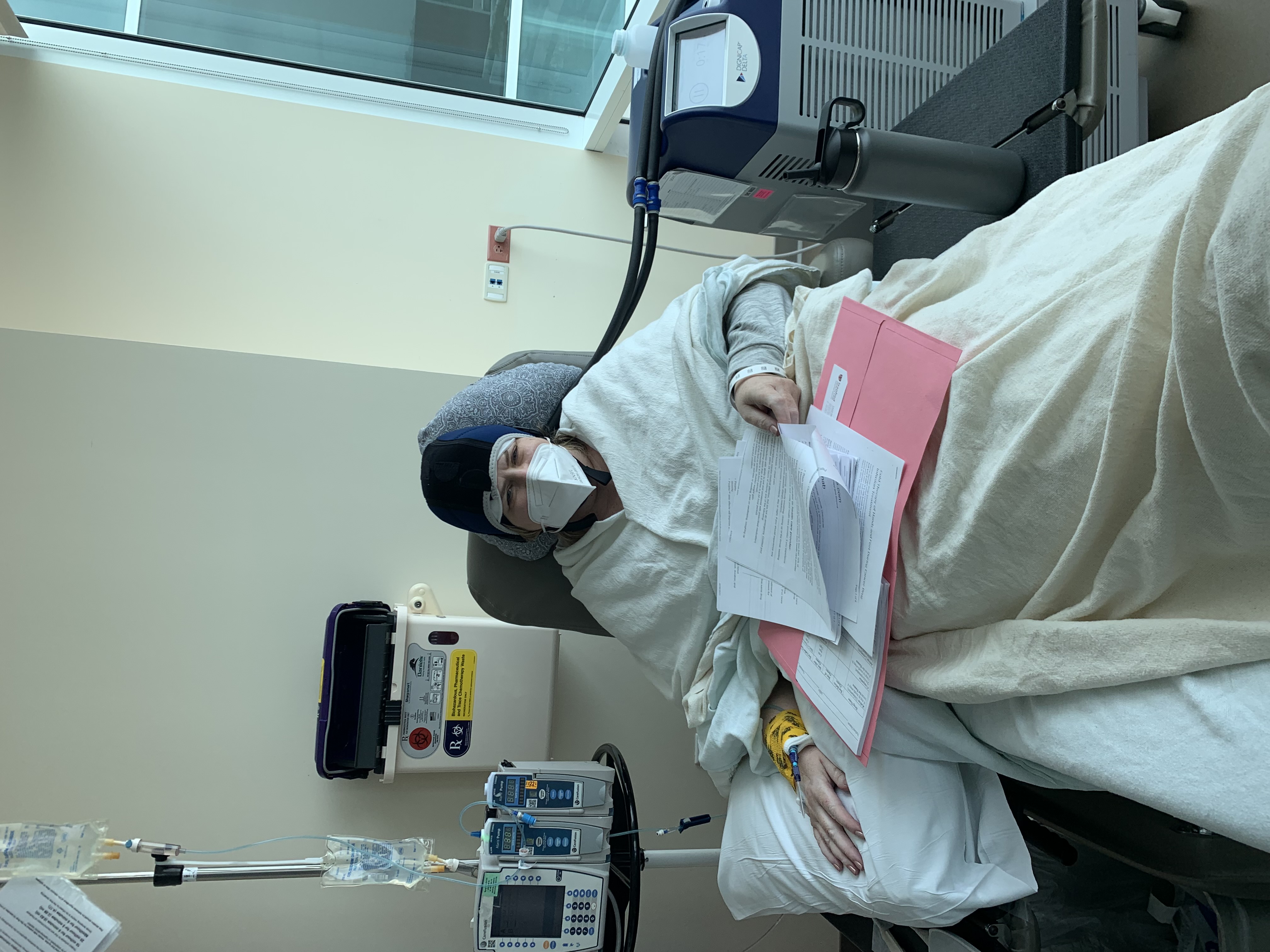

During chemotherapy, Kerivan had cold capping treatment, a scalp cooling therapy that protects hair follicles to help reduce hair loss.

A New Lease on Life

Kerivan felt very lucky to be treated at Stanford and is confident in her prognosis. “People suggested I plan a big vacation after my treatment ended or do something on my bucket list, but I don’t feel the need to do that,” she adds. “Being done with treatment is a weight off my shoulders, and now I have time to focus on the things that really matter: my family, my friends, and a job that I love.”

And Kerivan found a way to help others with HER2+ breast cancer: she’s participating in a clinical trial testing the safety of a vaccine aimed at preventing cancer recurrence by targeting the HER2 protein. Fauzia Riaz, MD, clinical assistant professor of medicine, is the principal investigator of the trial.

Kerivan enjoys walking her dog at the beach in San Francisco.

Kristy Kerivan thought her fatigue was from a cardiac issue and was not expecting her diagnosis: breast cancer that was HER2+, one of the more aggressive types. As senior administrative division director in the Department of Medicine’s division of oncology, she fortunately had immediate access to resources.

“I was panicked,” Kerivan says about her diagnosis. “The first person I went to was Heather Wakelee, MD, chief of oncology and also one of my bosses, and we talked through what I was facing. After that, it was a whirlwind.”

While Kerivan’s mom had previously been treated for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a noninvasive early form of breast cancer, Kerivan’s cancer had spread into breast tissue, making treatment lengthier and more complex.

And that treatment lasted a full year, starting with chemotherapy followed by lumpectomy surgery, radiation, and Herceptin, an IV medication that targets HER2+ receptors to stop cancer cell growth. Says Kerivan, “I feel fortunate that the cancer was caught early and that I had access to this medication because without it my prognosis would have been very different.”

During chemotherapy, Kerivan had cold capping treatment, a scalp cooling therapy that protects hair follicles to help reduce hair loss.

Cancer Care at Stanford

Kerivan likes to tell people that if you’re going to get cancer, you might as well get it while working in the division of oncology at a major academic institution like Stanford. “The care I received at Stanford was exceptional,” she says, referring to her 100-plus visits to Stanford during her yearlong course of treatment.

Kerivan has been in her current position since August 2020 and had worked as administrative director for Stanford’s Vera Moulton Wall Center for Pulmonary Vascular Disease for 17 years. Extremely familiar with the administrative side of health care, Kerivan found being a patient to be an eye-opening experience. “I was surprised about the things I didn’t know,” she explains. “While I understood how specialized cancer treatment is, I didn’t know just how complex cancer care is or how treatment impacts every area of your body.”

As a patient, she found it reassuring to visit areas she knew in passing as a staff person. “Because I was familiar with the hospital, it didn’t feel like a big, intimidating medical facility,” she says. “And from the people who checked me in, to the radiation therapists and the nurses who administered chemo — all of my personal interactions made me feel like people cared.”

As a comprehensive care center, Stanford offers an extensive array of cancer specialists. Allison Kurian, MD, professor of oncology and of epidemiology and population health at the Stanford School of Medicine, served as Kerivan’s breast oncologist and treatment physician, and her care team included a breast surgeon, a dermatology oncologist, a radiation oncologist, and a neuro-oncologist. Kerivan received periodic calls from a social worker and outreach specialist who helped her manage the emotional and nonmedical aspects of treatment.

“I felt lucky to have access to a wealth of specialists and support services that might not have been available to me at other institutions. I also felt a deeper appreciation for all the work conducted by Stanford researchers to find cures for cancer and other diseases. I like to think that, in some small way, I supported that progress,” she says.

From the people who checked me in, to the radiation therapists and the nurses who administered chemo — all of my personal interactions made me feel like people cared.

Kerivan enjoys walking her dog at the beach in San Francisco

Going the Extra Mile

An example of the exceptional care and support Kerivan received occurred one Easter Sunday while she was experiencing side effects from chemotherapy. Wanting to avoid going to the emergency room and possibly exposing herself to COVID-19 and other germs when her resistance was weakened, she was relieved to learn that the Infusion Center was open every day of the year. A nurse practitioner was able to see her that day and helped address her symptoms.

Kerivan took a medical leave at the beginning of her treatment, then worked a reduced 10-hours-per-week schedule from April to October 2022. This allowed her return to full-time work to be less of a shock, and it gave her ongoing support from colleagues, especially from her administrative and finance team. “I’ll never forget the many offers of help and messages of support from staff and faculty throughout this process,” she notes. Among the small acts of kindness were the groceries that Bhuvana Ramachandran, administrative division director in the division of hematology, bought and delivered to her. Kerivan’s bosses, Wakelee and Cathy Garzio, director of finance and administration for the Department of Medicine, were also extremely supportive while she returned to full health. “Cathy checked on me frequently to see how I was doing and sent me flowers and food via DoorDash,” recalls Kerivan. “Heather was a great medical resource for questions, and she made sure I was taking care of myself and not working too much. A big part of their support was what they didn’t do — they never made me feel pressured about work, and they let me do what I felt capable of.”

A New Lease on Life

Kerivan felt very lucky to be treated at Stanford and is confident in her prognosis. “People suggested I plan a big vacation after my treatment ended or do something on my bucket list, but I don’t feel the need to do that,” she adds. “Being done with treatment is a weight off my shoulders, and now I have time to focus on the things that really matter: my family, my friends, and a job that I love.”

And Kerivan found a way to help others with HER2+ breast cancer: she’s participating in a clinical trial testing the safety of a vaccine aimed at preventing cancer recurrence by targeting the HER2 protein. Fauzia Riaz, MD, clinical assistant professor of medicine, is the principal investigator of the trial.