Jason Gotlib’s Global Photography

Jason Gotlib’s Global Photography

Jason Gotlib, MD, MS, professor of hematology, has been passionate about photography for decades. His passion has taken him all over the world, from a planned trip to Patagonia in 2023 to Japan, New Zealand and many other far-flung locations (although he also loves the national parks closer to home). In a recent conversation, Gotlib reveals his deep love of photography, as well as his thoughts about what photography has meant to his life.

What is your role at Stanford?

I am a clinical trialist with a focus on developing new therapies for a group of diseases referred to as myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). These are chronic blood cancers characterized by overproduction by one or more types of blood cells, which can lead to an increased risk of clotting, bleeding, and transformation to acute leukemia. A large part of my work involves collaboration with lab-based researchers who have helped provide a biologic and molecular context for our clinical observations. I have led clinical development of several drugs that have received FDA approval, including the JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis and midostaurin and avapritinib for advanced systemic mastocytosis. I previously served as director of the hematology fellowship program and currently serve as vice chair of the Stanford Cancer Institute Data Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC).

How long have you been at Stanford?

September 2022 marks 32 years at Stanford for me. I arrived at Stanford in September 1990 for medical school and haven’t left. I undertook five years of medical school training, followed by three years of internal medicine residency training; five years of combined hematology/oncology fellowship training, including a master’s in clinical epidemiology; and one and a half years as an instructor in hematology, leading to my hire as assistant professor of hematology in 2005. I’ve been faculty for over 17 years. Although I describe myself as a “Stanford lifer,” I have some catching up to do relative to some of my mentors, who have been at Stanford for five to six decades, including the legendary hematologists Stan Schrier and Peter Greenberg.

When did you first become interested in photography?

When my sister and I were growing up in Queens, New York, and then New Jersey, my father was incessantly placing us in front of his camera. I can remember being annoyed by how often we were asked to pose for the lens, but his refrain was that we would someday appreciate having all these family photos. After retirement, his bedroom closet in Boca Raton, Florida, doubled as a sort of Library of Congress of his Kodachrome slide carousels. He has since digitized most of his collection. Every few months, he would email me a 40–50+ year-old photo: our young family decked out in ’70s fashion with the architectural décor of the day — plaid pants that matched our couch, oversized collars, and our faux wood–paneled den. His habit of emailing digitized photos greatly accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, when travel was put on hold. His photos were no longer an annoyance; they served up a nostalgic version of “The Story of Us” in order to cope with a world tossed upside down by the virus.

During the early days of the pandemic, new television production was put on hiatus, and many channels reverted to airing “The Best of” series from 30–40 years ago, including classic TV game shows or era-defining sports battles. Together with my father’s photos, these visual cues fed a rush of childhood memories. Most were very special, but some I had not thought about for decades and had purposefully put behind me. Sometimes, when the dam breaks, you can’t control how the floodwaters run. Everyone takes something different away from a photograph.

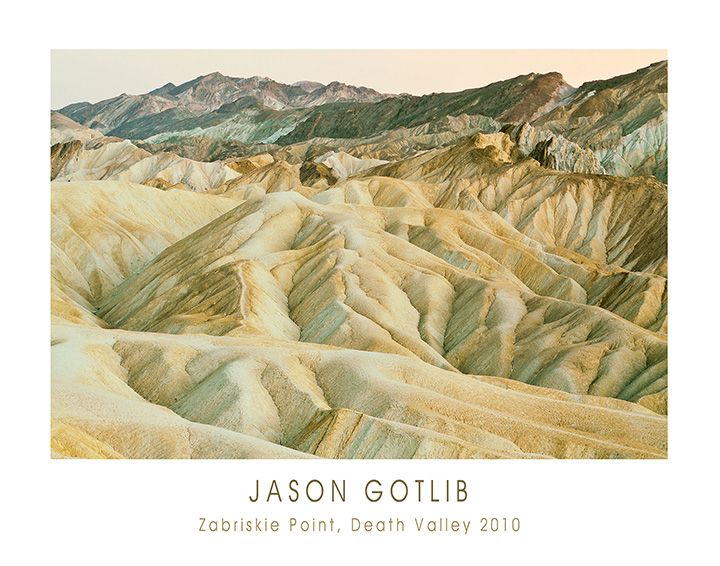

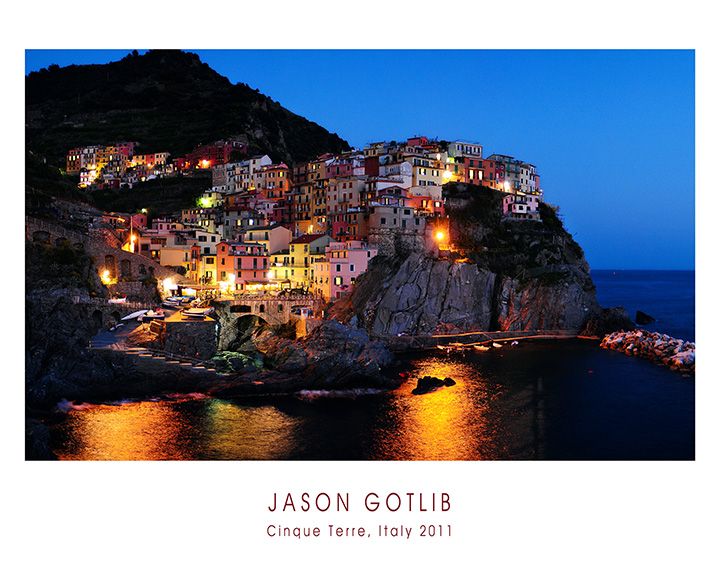

My love affair with photography began around the time of my Stanford medical school graduation in 1995, when I spent a month in Maui. I traveled the island, seeking the golden hours to photograph landscapes and sunsets and to gain experience with macro shots. I had my father’s camera in hand and one of my own — both traditional film cameras. It was during this trip that I left auto-focus behind and began experimenting with shutter speed and aperture so I could develop the craft of manual exposure. I purchased a tripod and graduated density filters, read countless books on composition and lighting, and tried to practice some of Ansel Adams’ photography fundamentals, including the art of pre-visualization. My growing interest in photography occurred in parallel with the revolution in digital cameras as well as post-processing software.

What kind of camera do you use? What’s the process you go through to develop photos?

I’m a Nikon devotee. Currently, I shoot RAW and JPEG using a D850 full-frame DSLR and a Z6 mirrorless. I use lenses that span the spectrum of focal lengths, including an ultra-wide-angle AF-S Nikkor 14–24mm F2.8G ED for expansive landscapes, a 24–70mm Z-mount lens for the mirrorless, and AF-S Nikkor zoom lenses that cover the 70–200mm and 200–500mm spectrum. I used the latter lens for 90% of my shots while I was on safari in Tanzania in 2019; I was able to get crisp shots of distant wildlife by placing the camera body and lens on a beanbag full of rice placed on my jeep’s window frame to act as a shock absorber against the bumpy dirt roads.

For my next trip to South America’s Patagonia, Atacama Desert, and the Uyuni Salt Flats in Bolivia in January 2023 (canceled twice due to COVID), I plan to purchase a Nikon Z9, which is their new flagship mirrorless camera. I use the program Lightroom for post-processing my photos, but I try to get the best shot in camera to minimize the time spent on optimizing photos after the fact. I’ve worked with a few custom photography services; now I turn almost all my prints into gallery-style acrylic mounts, some which are up to 5 by 7 feet in size. They cover the walls of my house, and I have hung several of them in the hallways of our staff offices at the Cancer Center.

What are some of the difficulties involved in photography?

Digital cameras have democratized photography for the masses, allowing untold numbers of hobbyists to take high-quality photos at low cost. However, many iconic landscape locations, many of which were a best-kept secret of semi-pro and professional photographers, have lost their anonymity and have been overrun by tourists. In order to secure a camera shot, I have to sometimes wake up at 3:00 or 4:00 a.m. with headlamp in tow to stake my ground for a shot at dawn. This was the case for my shot of Mesa Arch in Canyonlands in March 2020, just before Moab closed down for COVID.

In February 2021, I photographed Firefall in Yosemite. This can be captured during a two-week block of time in February when the sun hits El Capitan, and Horsetail Falls glows orange when it’s backlit by sunset. When I visited in 2008, I saw only a handful of photographers trying to capture the ephemeral event. In 2021, despite COVID, the number of photographers had swelled to easily over some 1,500 on one evening, in a viewing area less than an acre. Several years ago, I set up my tripod two hours early for a sunset shot of Utah’s Delicate Arch. I was part of a 50-person gallery of (usually patient) photographers who had to give up on courteous pleas — in favor of more vocal rebukes — to ask tourists not to loiter endlessly in front of the Arch taking selfies. We were all desperate to capture a clean shot of the Arch before the sun barreled below the horizon.

What’s your favorite thing about photography?

Photography serves many functions for me. First, traveling to the national parks and other landscapes is restorative. It’s quality, quiet time with my wife, Lenn, who loves to hike. While caring for patients with leukemia has been immensely rewarding, the journey is filled with too many fleeting acquaintances — close relationships with patients (and also mentors) who have passed, as well as trainees who have moved on from our program. I find the national parks are a counterbalance to this blur of human turnover. The parks will always be there when I choose to return. My favorite spots will change little during my lifetime. This constancy is comforting. A pause in the middle of nature — a little bit of stasis to recalibrate an otherwise hectic life — is more than welcome. However, I do worry that the assault of climate change on the parks may require me to adjust my expectations of what the parks will look like when I return.

How do you get a really good photograph?

Getting the good shot requires several things: knowing how to get the most out of your camera’s functionality, tack-sharp lenses, a sturdy (but lightweight) tripod, a cable release so I don’t have to touch my camera, and, most importantly, waiting for the right light. And sprinkle in patience, pre-trip research, and luck. I’ll set up my tripod for hours around the golden hours to get my shot. For all the times I’ve checked all these boxes, I can count many more times where I’ve failed miserably. I remember one time in Kyoto, Japan, where I was bumbling around with my clunky tripod taking pictures of architecture of the Geisha district because I had given up on capturing an actual geisha. Lenn tapped my shoulder, and I turned around and barely glimpsed a geisha before she ran into an ochiya, one of the teahouses used for entertaining guests. Meanwhile, my wife caught an amazing still of the geisha with a blurred background on her iPhone, one of my all-time favorite photographs. Sometimes you have to know when to free yourself of your tripod.

Perhaps part of the zen of photography, like other aspects of life, is managing expectations. When you hit the road or hop on a plane for a shoot, it’s like playing casino slots. You don’t know if you’ll hit triple 7s with a stunner photo or leave empty-handed. Mother Nature has a lot to say, and I’m often playing the Goldilocks game with her. I don’t want completely clear skies or completely cloudy skies, but just enough clouds to create interesting patterns of reflected light. I’ve stopped becoming dispirited about trips washed out by weather — as the next trip could end up with a surfeit of photo ops. It all evens out in the end. However, if I can get two or three photos a year that I really love, that’s a good year.

What are some of your favorite photographs and memories of taking them?

During a visit to Glacier National Park, I was shooting snow-capped mountain peaks; this time, Lenn’s shoulder tap came in time, and she whispered, “You may want to turn around.” I did so slowly and saw two white mountain goats just behind me, camouflaged by the snowy background, another one of my favorites. The unexpected shots can be the most rewarding and memorable. Lenn has a great eye and has been so generous in her support of my passion for photography, waiting with me for hours just for the right light to cast its glow on my subject.

On another trip, I spent five days doing a photography workshop in the Grand Tetons, but it was cloudy and raining the whole time. The group departed for home, but Lenn and I decided to stay. Our persistence paid off; at twilight, the skies opened up with the most spectacular hues of purples, reds, and yellows. Meteorologists talk about one-in-a-thousand-year floods. For me, this may have been a one-in-a hundred-year night; we raced around the park — from Oxbow Bend to along the Grand Teton Mountain Range — before the deep colors faded. It was a hall-of-fame photographic experience, and the images from that evening line the walls of my house.

Some of my favorite shots are the ones that take the most work to get. One is from a nine-hour backcountry hike in Zion National Park, following the path of the Virgin River to the Archangel Cascades and the Subway, to a rock formation that creates a tunnel of light leading to glowing blue and green tidal pools. On my first attempt I fell short; I returned with Dr. Jim Malone (we started hematology fellowship together in 1998) and his wife, Jessica, who is a nurse. Jim’s military experience and leadership skills (he’s a colonel in the Army Reserve) successfully navigated us along the challenging terrain. It’s an experience we look back upon fondly, and we have talked about going back for an encore.

Where has your photography taken you?

Besides the Grand Tetons and Utah national parks, I’ve been able to collect 20 of the 63 U.S. national parks. I’ve photographed in many European countries, Canada, Alaska, China, Israel, Jordan (Petra), Japan, Cuba, and New Zealand (including photography of White Island the year before its active volcano exploded, killing 22 people), and Tanzania in 2019, where I spent time with the Maasai from Olmoti village, volunteering time in their medical clinic and learning about their local culture and customs. Lenn purchased a black sheet in our pre-Africa travels in Amsterdam, and we hung it on the medical clinic wall, and I took many portraits of the Maasai. I borrowed this idea from National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore and his photo ark project, whose mission is to document species before they disappear. It was a bonding experience, and many of them saw pictures of themselves for the first time in my camera’s LCD screen. With the safari that followed, it was the most rewarding experience I’ve participated in.

After my January 2023 Patagonia trip, my bucket list includes a trek to Everest Base Camp, Bhutan, Iceland’s chain of volcanoes, and a trip with National Geographic to Antarctica, South Georgia Island, and the Falkland Islands to walk among penguins and experience glacier calving.

How do you think your hobby has influenced your work at Stanford?

Photography can be a wonderful icebreaker. Patients open up about their own trips and memories, and many times this segues into their own love of photography or other hobbies. Such conversations allow me and the patient to learn more about each other and our families. It’s an organic conversation but can serve as a useful distraction from the constant focus on their illness. For my colleagues, I hope my photos excite them to travel. Certainly, I get excited when I hear their travel stories. And similar to our patients, it opens up an opportunity to discuss their lives and how they are pursuing their passions outside of the hospital.

I am a huge fan of the chef Anthony Bourdain, although he apparently preferred the label “writer” or “storyteller.” After his suicide in 2018, many pontificated about what made him and his food and travel show Parts Unknown so special. His suicide devastated many people who had no personal relationship to him. I am one of them. Why? He had a preternatural ability to break bread with and listen to people from disparate cultures — sometimes marginalized or poorly resourced, or with viewpoints that may reside on the other side of the political spectrum. He was an empath who rooted for the underdog and cast his guests in a dignified light. In the documentary about his life, Roadrunner, one of his friends explained, “It was almost never about food. It was about Tony learning how to be a better person.” His life and suicide reminded me of the line from Alan Ball’s 1999 film American Beauty, where the character Ricky Fitts says, “Sometimes there’s so much beauty in the world, I feel like I can’t take it.”

Looking forward, I see photography, like Bourdain’s sit-down meals, as a means of engaging other peoples and extending my worldview. I was able to accomplish this to some degree with the Maasai. I can’t help but think this would add great value and perspective to my professional and personal life.