Open Science at Stanford

Promoting Data Access, Credibility, and Reproducibility For All

Open Science at Stanford

Promoting Data Access, Credibility, and Reproducibility For All

Ten years ago, Amgen, a biotech company in Los Angeles, tried to replicate what it considered to be the hundred most important studies done in cancer biology. The results of the project showed that Amgen was able to replicate only six study findings out of 53 landmark cancer papers. This study from Amgen caught the attention of many people in the field, who worried about the scientific credibility of the 53 cancer papers, according to Mark Musen, MD, PhD, director of the Stanford Center for Biomedical Informatics Research. Lines of investigation were launched on the basis of those papers, as the assumptions that underpinned considerable research activity in the field were suddenly called into question.

Musen is working to fix this problem of data management and spreading the information to all relevant people. His goal is to create guidelines and templates that will give researchers the tools needed to duplicate their work. This comes on the heels of an October 2020 announcement of new National Institutes of Health (NIH) requirements that many researchers will soon have to follow.

The National Institutes of Health issued new requirements that many researchers will soon have to follow.

NIH Requirements

Scientists dealing with billions of pieces of raw data will find it much easier to do their work after Jan. 25, 2023. That’s when the NIH will adopt a new Data Management and Sharing Policy. Researchers funded by the NIH will be required to submit a formal plan detailing how they will share their research data. The new policy, in part, follows principles first laid out in a paper published in 2016 in Scientific Data.

The Scientific Data paper argued for scientific data to be findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR). That is, they need to be easy to find in a common database, accessible by those with disabilities, able for others to use and exchange the information, and able to be used again. The creation of FAIR Principles provides an essential set of guidelines for stakeholders who wish to go FAIR.

The NIH’s new policy requires that researchers share all scientific data so that others can more easily use findings from previous studies in future studies. Furthermore, researchers must include a plan for sharing their data whenever they apply for NIH funding. The NIH will cover the costs of data collection, sharing, and storage.

Many leaders in the field of biomedical informatics see the NIH policy as a giant step toward Open Science, a concept that makes science much more accessible, inclusive, and available for everyone. Open Science seeks to eliminate the barriers to access of data and to provide scientific credibility by allowing everyone to verify study findings. Stanford experts are in favor of the Open Science concept, but they differ in how they approach and use it.

Purvesh Khatri, PhD

Open Science in Action

Purvesh Khatri, PhD, an associate professor of biomedical informatics research and an associate professor in the Institute for Immunity, Transplantation and Infection, has used Open Science to create new findings using existing data. Khatri and his lab were able to comb through many publicly available data sets to examine and analyze what factors could lead to new developments in tuberculosis (TB) patterns in gene expression.

Khatri’s research in TB led to the development of TB testing using only finger-stick blood samples. The Khatri lab found that three gene signatures could be used to diagnose TB. Using publicly available data that represented various real-world patient populations, the lab concluded that three genes could indicate whether someone has TB. These findings led the lab to move

past the discovery stage and produce a clinical result in five years.

For Khatri, the process of searching through different publicly available data remains a challenging endeavor. He says, “We know that these data sets exist out in the public domain, but we have to go out and look for them. Looking for this information is exhausting and labor-intensive. Since there is no centralized method of labeling data, every single piece of data could have different labels for many various things. Researchers who are reading these papers may not be able to find the information they need to get the information. There has to be a solution to this problem.”

Reproducibility: Approaching Scientific Data Like a Librarian

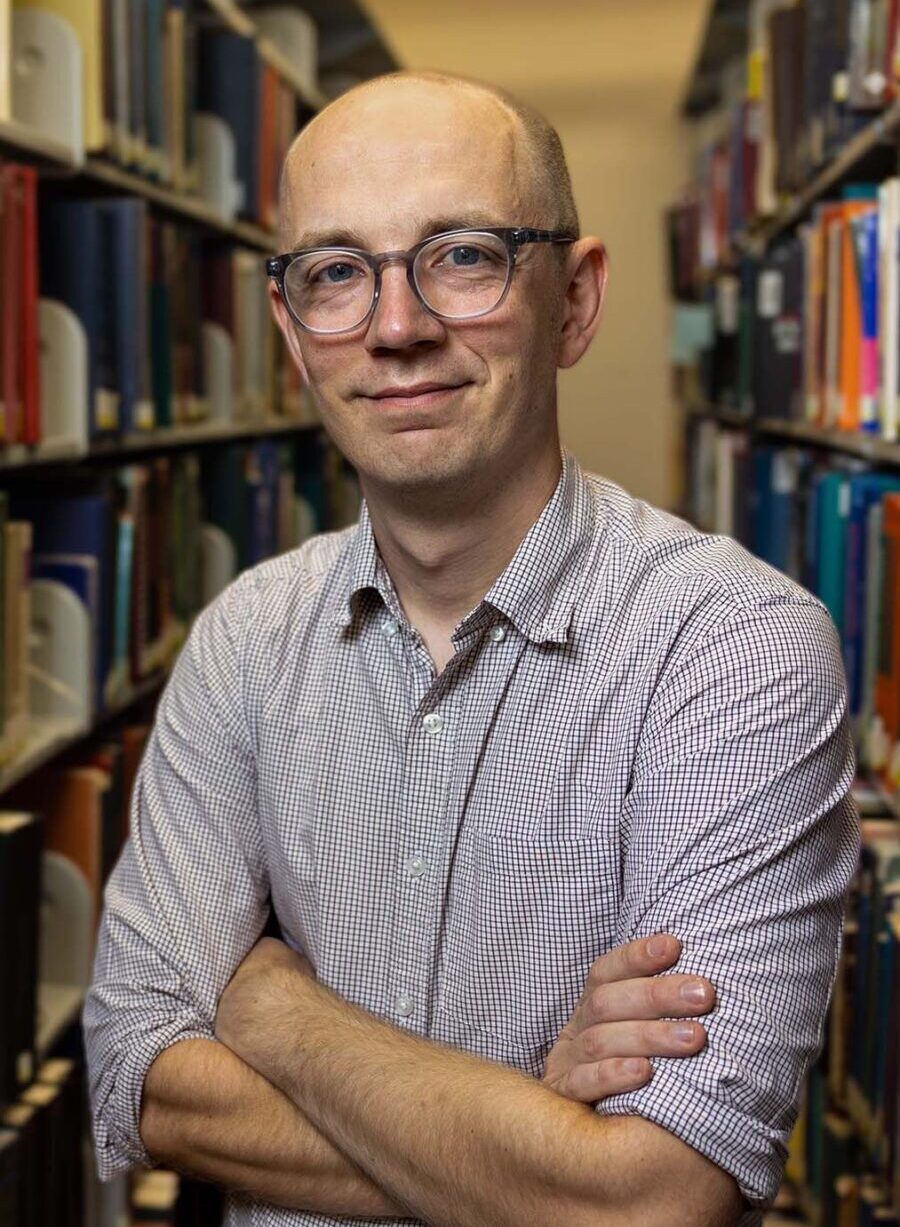

Reproducibility helps interested researchers re-create a study so they can follow similar steps when forming their own results. Reproducibility also allows other researchers to find and share the information with ease. “I became interested in all of this because Open Science is actually more broadly about making science itself accessible and transparent,” says John Borghi, PhD, manager of research and instruction at Lane Medical Library at Stanford.

Borghi plays a large role in educating Stanford School of Medicine faculty about the new NIH data-sharing requirement, and he helped Lane Library acquire a license for Dryad, a highly used, general-purpose data repository that was developed by the University of California to make it easy to archive and share scientific data sets.

Imagine a hobbyist with all the pieces of a complicated model car laid out in front of him, but with no instructions. He could end up with a completed model car, but he may have put some pieces in the wrong places. “Open Science practices really help you facilitate a step-by-step process that is much more like building a model where you have instructions that make sense,” says Borghi. “If two people have all the pieces readily available, then one person will create one version of the model, and the other may create another version. Without instructions on how to duplicate the model, you can come up with a vastly different outcome.”

“I was a neuroscience researcher before I was a librarian,” Borghi explains.

Photo Caption Here

“I was not thinking about the people who would read our data. We were creating data sets and maybe sharing them, but not really describing them in such a way that they could be found.” Creating and standardizing metadata and creating methods and forms to list them ensures that researchers can properly file and store data for researchers who wish to look up studies.

Metadata is a type of data that describes information inside something like a written document or file, which informs users of the content. Just as an abstract gives basic information about a scientific journal article, metadata offers the same for data. Consider a researcher who locates a book in a library on a subject of interest. Metadata would inform the researcher of what the book holds and where to find that information. The book metadata would include the title, subtitle, publication date and ISBN, keywords and key phrases, book description, and author bio. This information would be listed in the metadata, and the book’s information would be cataloged, thereby easily found in a library, similar to a data repository.

“Open Science seeks to eliminate the barriers to access of data and to provide scientific credibility by allowing everyone to verify study findings.”

–Steve Goodman, MD, MHS, PhD

He plans to work with Borghi this fall to survey School of Medicine investigators and learn how databases are being managed to determine training and support needs. SPORR is also planning a school-wide symposium on Jan. 23, 2023 — the day the NIH requirements go into effect — to educate faculty and provide on-site consultation for investigators. It is also presenting a three-week mini-course on the topic for trainees during Stanford’s winter 2023 term.

Goodman stresses that the SPORR team is looking to support research groups that need assistance and to identify those that use best practices, recognizing them through prizes and dissemination. As Goodman says, “Our responsibility as an initiative and as a school is to make rigorous data handling easy; each researcher shouldn’t have to invent their own wheel. We want to help Stanford investigators learn from each other about what works best here.”

Open Science practices really help you facilitate a step-by-step process that is much more like building a model where you have instructions that make sense.

– John Borghi, PhD

Open Science practices really help you facilitate a step-by-step process that is much more like building a model where you have instructions that make sense.

– John Borghi, PhD

Mark Musen, MD, PhD

CEDAR is trying to streamline the authoring of this metadata, which will enable researchers to eliminate deviations when describing different data in the same subject. As mentioned above, the process of combing through different publicly available data is a continuing challenge for scientists like Khatri. The lack of standard terms within the metadata makes it hard for investigators to find what they’re looking for.

CEDAR’s primary contribution is to ensure that new metadata adheres to whatever standards the research community has settled upon. Once it’s simplified and centralized, researchers will have an easier time finding the information they need to continue with their research. As Musen explains, “The good news — or the bad news, depending on your perspective — is that scientists didn’t start putting their data in online repositories until the 1980s.” There has been a lot of data since the 1980s, and not all of it adheres to proper metadata search terms. However, there is hope.

The National Science Foundation has issued a grant to a small business called Metadata Game Changers to integrate CEDAR into Dryad, the general-purpose data repository. The expectation is that people who upload data sets into Dryad will be able to use CEDAR to create appropriate metadata. For Borghi, who is working with School of Medicine faculty, integrating CEDAR into Dryad will enable faculty to share data using Dryad if there is no other appropriate repository for them to use — just in time for the new NIH policy.

CEDAR is a starting point for researchers and scientists to correct the mistakes of past studies and to modernize how information from those studies is shared. If all things come together, using Open Science and FAIR principles will ensure that future studies based on previous landmark science papers will be able to reproduce results with few to no problems. What a difference that would have made for Amgen back in 2012!