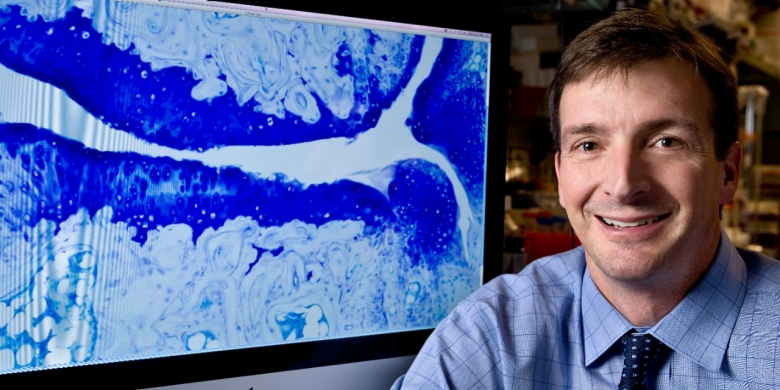

William Robinson, MD, PhD

Revealing Microbial Triggers of Autoimmune Disease

William Robinson, MD, PhD

Revealing Microbial Triggers of Autoimmune Disease

For decades, scientists have suspected that many autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis (MS) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), might be triggered by infections. Now, Department of Medicine researchers have shown exactly how this happens for two common autoimmune diseases — MS and RA. William Robinson, MD, PhD, the James W. Raitt, MD, Professor and chief of immunology and rheumatology, and colleagues discovered how infection with the Epstein-Barr virus, a common herpes virus, can trigger MS, as well as how bacteria normally found in the mouth can breach into the bloodstream to cause RA flare-ups in people with gum disease.

“We’re finally starting to gain insights into what actually causes these very prevalent autoimmune diseases,” says Robinson, who led the work. “In the near future, this may fundamentally change how we treat or prevent these diseases.”

In the new studies, Robinson’s team used a technology that they developed at Stanford over the last decade. It allows them to sequence the antibody repertoire of human B cells — the immune cells that produce antibodies. The gene sequences tell them exactly what antibodies each B cell is making.

“In the old days, someone’s entire thesis project might have been sequencing the antibodies of a few B cells, and it would take years,” says Robinson. “With this approach that is now available commercially, we can now sequence thousands of B cells at once. This is an incredibly powerful tool.”

In healthy individuals, the antibodies made by B cells recognize only viruses and bacteria that are harmful to the body; in those with autoimmune disease, however, antibodies attack the body’s own healthy tissues. In MS, for instance, the immune system attacks the protective coverings of nerve fibers, causing numbness, muscle weakness, and fatigue. However, the exact antibodies and immune response that mediate MS were not known.

Robinson’s group isolated thousands of B cells from the spinal fluid of patients with MS and sequenced the antibody repertoires of those B cells to discover what antibodies they produced. Then, the researchers tested those antibodies to see whether they reacted with viruses or healthy human tissue. Their experiments revealed one antibody that recognized both Epstein-Barr virus and a protein, called myelin, made in the brain and spinal cord.

“This means when the immune system attacks Epstein-Barr virus, in some people it also ends up attacking molecules in the central nervous system,” says Robinson.

His group went on to show that approximately a quarter of all patients with MS have detectable levels of these Epstein-Barr antibodies that cross-react with myelin. The findings, published in 2022 in the journal Nature, suggest that in the future, a vaccine against Epstein-Barr virus could help prevent MS, and a drug that blocks the cross-reactive viral antibodies has the potential to treat the disease.

With this approach that is now available commercially, we can now sequence thousands of B cells at once.

Using the same B-cell sequencing technology, Robinson and his colleagues studied the immune cells of people with RA, a chronic disease that causes joint inflammation and pain in approximately 0.5% of the population. When Robinson’s team sequenced B cells from patients with active flares of RA, they discovered antibodies that bind mouth bacteria and cross-react with joint tissues.

Through a series of experiments, the researchers showed that in people with periodontitis, or gum disease, bacteria from the mouth breach into the bloodstream and cause an immune response. In some people, the oral bacteria activate an autoimmune response that causes RA flares. The results were published in February in Science Translational Medicine.

“Right now, to treat RA, we give patients very broad-acting drugs that block whole pathways of the immune system,” says Robinson. “But if a subset of RA arises from breakdown of the gums, letting bacteria into the bloodstream, what if we focus more on oral health?”

Robinson says that these two major findings are likely just the tip of the iceberg on how viruses and bacteria can induce or mediate chronic autoimmune disease. More work is needed to make these connections and to understand why viruses and bacteria trigger long-term autoimmune disease in only some people.

“Stanford is one of the best places in the world to be working on this kind of translational immunology,” Robinson adds. “It’s an incredibly collaborative environment, and we have experts studying all aspects of rheumatologic diseases, along with clinical investigators running trials to translate these types of findings to patients.”

For decades, scientists have suspected that many autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis (MS) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), might be triggered by infections. Now, Department of Medicine researchers have shown exactly how this happens for two common autoimmune diseases — MS and RA. William Robinson, MD, PhD, the James W. Raitt, MD, Professor and chief of immunology and rheumatology, and colleagues discovered how infection with the Epstein-Barr virus, a common herpes virus, can trigger MS, as well as how bacteria normally found in the mouth can breach into the bloodstream to cause RA flare-ups in people with gum disease.

“We’re finally starting to gain insights into what actually causes these very prevalent autoimmune diseases,” says Robinson, who led the work. “In the near future, this may fundamentally change how we treat or prevent these diseases.”

In the new studies, Robinson’s team used a technology that they developed at Stanford over the last decade. It allows them to sequence the antibody repertoire of human B cells — the immune cells that produce antibodies. The gene sequences tell them exactly what antibodies each B cell is making.

“In the old days, someone’s entire thesis project might have been sequencing the antibodies of a few B cells, and it would take years,” says Robinson. “With this approach that is now available commercially, we can now sequence thousands of B cells at once. This is an incredibly powerful tool.”

In healthy individuals, the antibodies made by B cells recognize only viruses and bacteria that are harmful to the body; in those with autoimmune disease, however, antibodies attack the body’s own healthy tissues. In MS, for instance, the immune system attacks the protective coverings of nerve fibers, causing numbness, muscle weakness, and fatigue. However, the exact antibodies and immune response that mediate MS were not known.

Robinson’s group isolated thousands of B cells from the spinal fluid of patients with MS and sequenced the antibody repertoires of those B cells to discover what antibodies they produced. Then, the researchers tested those antibodies to see whether they reacted with viruses or healthy human tissue. Their experiments revealed one antibody that recognized both Epstein-Barr virus and a protein, called myelin, made in the brain and spinal cord.

“This means when the immune system attacks Epstein-Barr virus, in some people it also ends up attacking molecules in the central nervous system,” says Robinson.

His group went on to show that approximately a quarter of all patients with MS have detectable levels of these Epstein-Barr antibodies that cross-react with myelin. The findings, published in 2022 in the journal Nature, suggest that in the future, a vaccine against Epstein-Barr virus could help prevent MS, and a drug that blocks the cross-reactive viral antibodies has the potential to treat the disease.

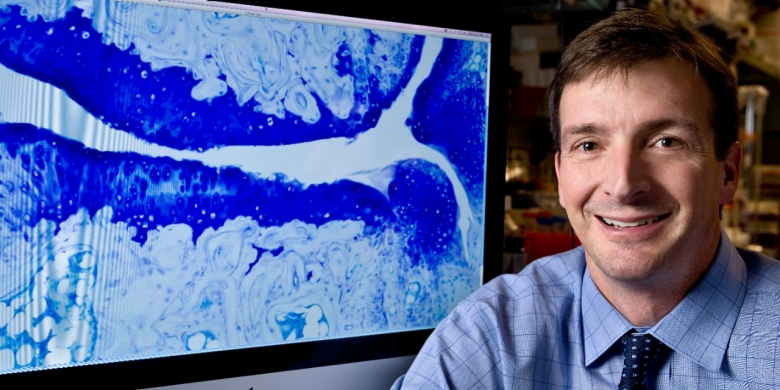

Click image above to expand

With this approach that is now available commercially, we can now sequence thousands of B cells at once.

Using the same B-cell sequencing technology, Robinson and his colleagues studied the immune cells of people with RA, a chronic disease that causes joint inflammation and pain in approximately 0.5% of the population. When Robinson’s team sequenced B cells from patients with active flares of RA, they discovered antibodies that bind mouth bacteria and cross-react with joint tissues.

Through a series of experiments, the researchers showed that in people with periodontitis, or gum disease, bacteria from the mouth breach into the bloodstream and cause an immune response. In some people, the oral bacteria activate an autoimmune response that causes RA flares. The results were published in February in Science Translational Medicine.

“Right now, to treat RA, we give patients very broad-acting drugs that block whole pathways of the immune system,” says Robinson. “But if a subset of RA arises from breakdown of the gums, letting bacteria into the bloodstream, what if we focus more on oral health?”

Robinson says that these two major findings are likely just the tip of the iceberg on how viruses and bacteria can induce or mediate chronic autoimmune disease. More work is needed to make these connections and to understand why viruses and bacteria trigger long-term autoimmune disease in only some people.

“Stanford is one of the best places in the world to be working on this kind of translational immunology,” Robinson adds. “It’s an incredibly collaborative environment, and we have experts studying all aspects of rheumatologic diseases, along with clinical investigators running trials to translate these types of findings to patients.”