A COVID Trial Pitches a Tent in the Great Outdoors

COVID team members at work in the tent

The CTRU tent under a beautiful sky

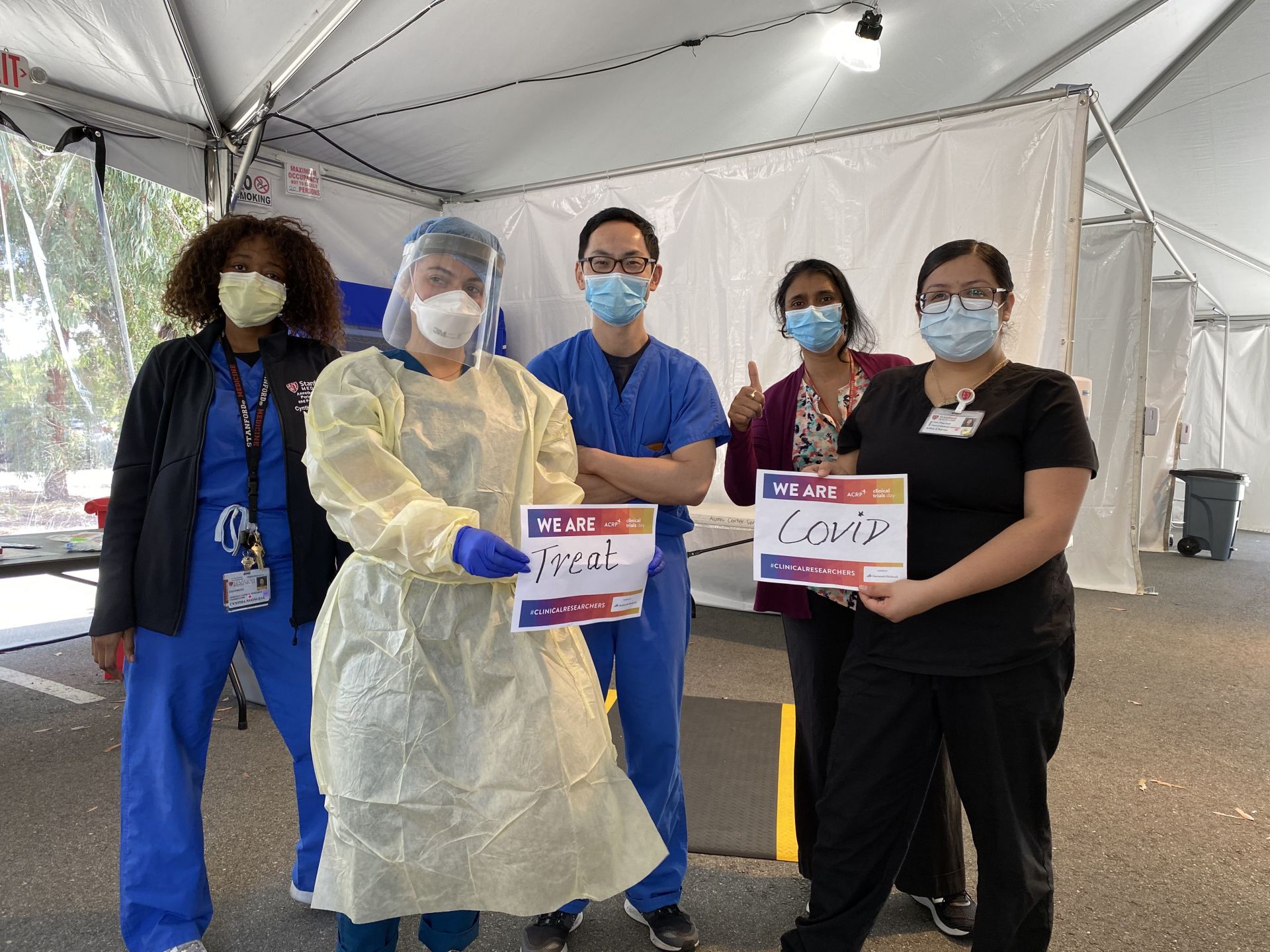

Team Treat COVID staff

Keeping up morale in the tent with Team Treat COVID

“People who are involved in clinical trials are

often really motivated by doing good for the world.

These people who join these clinical trials are heroes”

“People who are involved in clinical trials are often really motivated by doing good for the world. These people who join these clinical trials are heroes”

Matching jackets for Team TreatCOVID, Clinical Trials Research Unit

Working in the Tent

Jason Andrews, who has worked on many global health initiatives, from a renovated grain shed in Nepal to a renovated truck in Brazil, was a little more familiar with nontraditional medical environments. But, he adds, “it was exciting to find creative ways to extend access to these investigational treatments for COVID to patients who otherwise might not have options.”

He worked regularly in the tent, as well as serving as a co-investigator on several of the studies and principal or co-principal investigator on others, and found the experience invigorating. “There was a real esprit de corps among the CTRU team, particularly in the earliest days,” he remembers. “There was a strong can-do spirit, with all of us finding solutions to overcome obstacles and fulfill our commitment to the patients. It was really fulfilling to be part of a team that was so focused and committed.”

Prasanna Jagannathan also worked regularly in the tent and was familiar with clinical trials (although not in this particular setting.) “As the saying goes,” he says, “in the lambda study, we built the plane (tent) as we flew (occupied) it.” He was part of the early group of staff who worked seven days a week during the tent’s early days, and also served as a co-PI on the first study.

Bonnie Maldonado was no stranger to unique clinical trials, having set them up in small villages in Veracruz and in the highlands of Chiapas, Mexico, among Indigenous Nahuatl and Mayan populations, among many others, but she agrees that there were distinct challenges involved in this work. “Very early on, most of the work was actually being done by our infectious diseases faculty,” Maldonado remembers, “seven days a week, on top of their routine clinical, teaching, and research responsibilities. The biggest challenge so far has been trying to build new programs and clinical trials de novo, from identifying a novel therapeutic to understanding the construction and equipment needed to maintain the COVID CTRU tent and buildings.”

She took her turn as the PI of one of the studies and co-PI of others, working weekly in the tent to enroll and attend patients, and has now moved on to thinking about how to build new strategies for therapeutic studies.

Julie Parsonnet also helped recruit, monitor, and treat patients. She is the PI for the camostat trial and helped design and implement the lambda trials (not to mention her other projects and duties).

Hector Bonilla, who was part of the original team voting for the tent and its location, was invited to be part of the first outpatient trial of lambda. He remembers that the tent “became our second home” and calls the work “the opportunity of a lifetime.” He worked nights (recruiting mainly Spanish speakers for the trial) as well as days (enrolling patients, collecting samples, drawing blood, and answering patient questions, among many other duties). He remembers colleagues doing the same, sharpening their Spanish as the trial went along. “It was a real village,” he concludes, remembering how the work and interactions with colleagues made him “feel proud and respected by each division member.”

Chaitan Khosla, who worked mostly offsite, was “in complete awe of the clinical team in the tent,” he says. “And not just the doctors but also the clinical staff over there—the nurses, the clinical research coordinators, and the other support staff.”

“There is no way we could have done any of this without the staff,” Upi Singh agrees. “They also took a chance early on in the pandemic, trusting that they would be safe. And they very quickly became addicted to the positive impact of the work and the connections with patients.”