by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2018, creating 2018

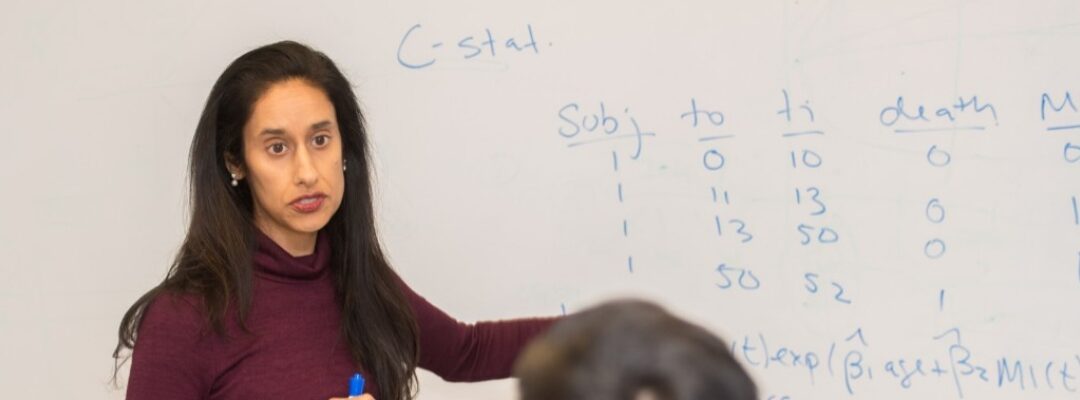

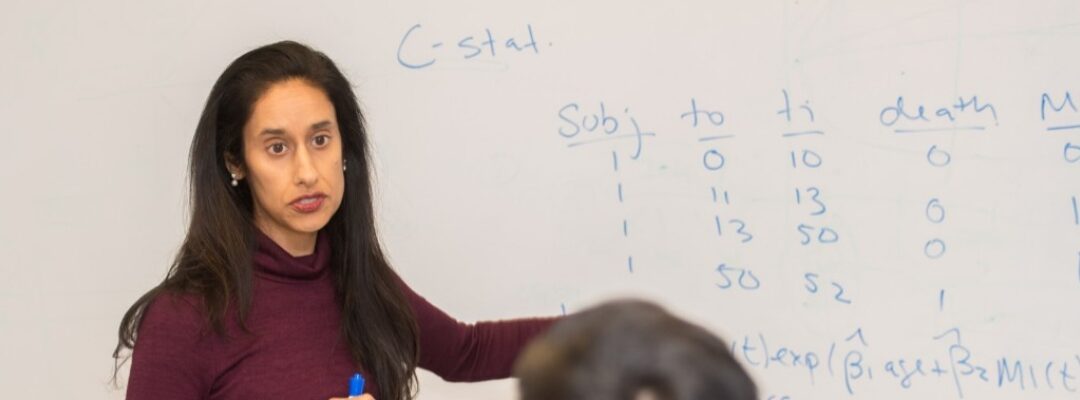

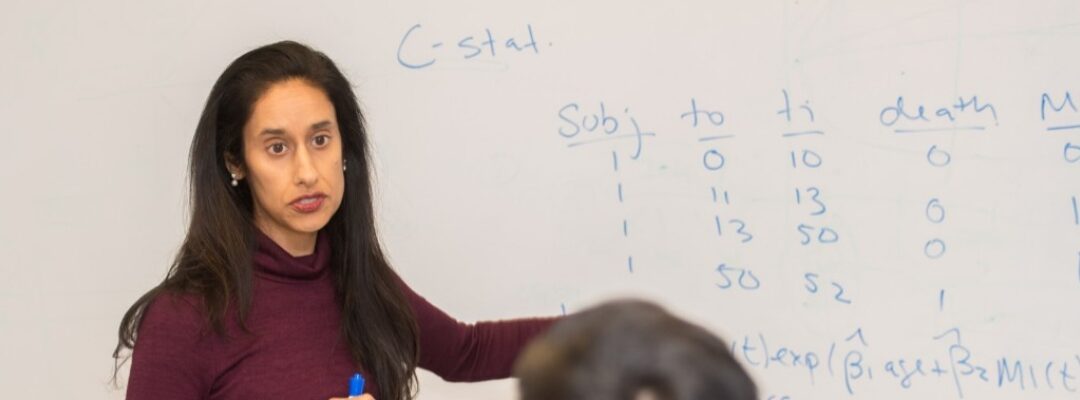

Manisha Desai, PHD, Professor of Biomedical Informatics Research Quantitative Sciences Unit: It’s Not About the Sample Size Manisha Desai, PHD, Professor of Biomedical Informatics Research Quantitative Sciences Unit: It’s Not About the Sample Size...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2018, creating 2018

Ami Bhatt, MD, PhD The New Stanford Center for Arrhythmia Research: A Multidisciplinary Approach at Heart Ami Bhatt, MD, PhD The New Stanford Center for Arrhythmia Research: A Multidisciplinary Approach at Heart The Division of Cardiovascular Medicine has launched the...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2018, creating 2018

Pamela Kunz, MD, assistant professor of medicine and director of the Neuroendocrine Tumor Program Conversations on Combating Cancer Pamela Kunz, MD, assistant professor of medicine and director of the Neuroendocrine Tumor Program Conversations on Combating Cancer In...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2018, creating 2018

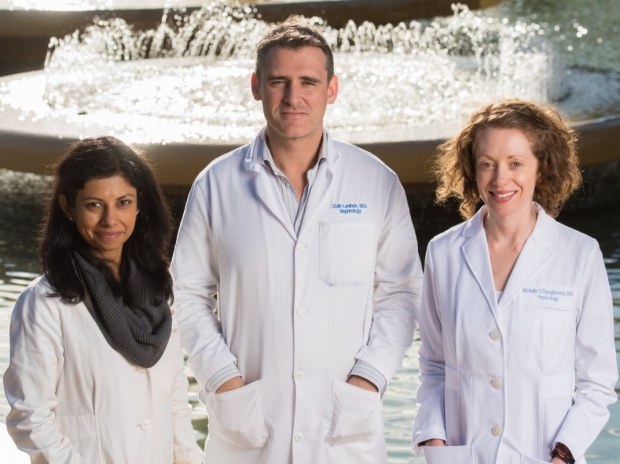

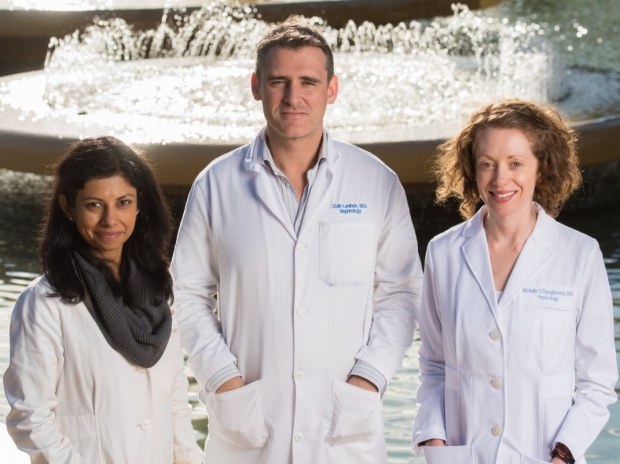

From left: Drs. Shuchi Anand, Colin Lenihan, and Michelle O’Shaughnessy are addressing some of nephrology’s toughest challenges. Young Nephrologists Asking Big Questions About Kidney Diseases From left: Drs. Shuchi Anand, Colin Lenihan, and Michelle...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2018, sharing 2018

Lisa Shieh, MD, PhD (right), makes a point about quality improvement with medical residents Residents’ Elective Tackles Quality Improvement Research Lisa Shieh, MD, PhD (right), makes a point about quality improvement with medical residents Residents’ Elective Tackles...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2018, sharing 2018

Chad Weldy, MD, PhD The Tipping Point: How Stanford’s Translational Investigator Program Supports—and Propels—the Careers of Early Physician-Scientists Chad Weldy, MD, PhD The Tipping Point: How Stanford’s Translational Investigator Program Supports—and Propels—the...