by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Rebuilding Community Connections 2023

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits Dr. Andrew Enslen, a global health track resident at the time, spent six weeks in the spring of 2023 working with UGHE in a local district hospital, functioning as a consultant attending...

by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Rebuilding Community Connections 2023

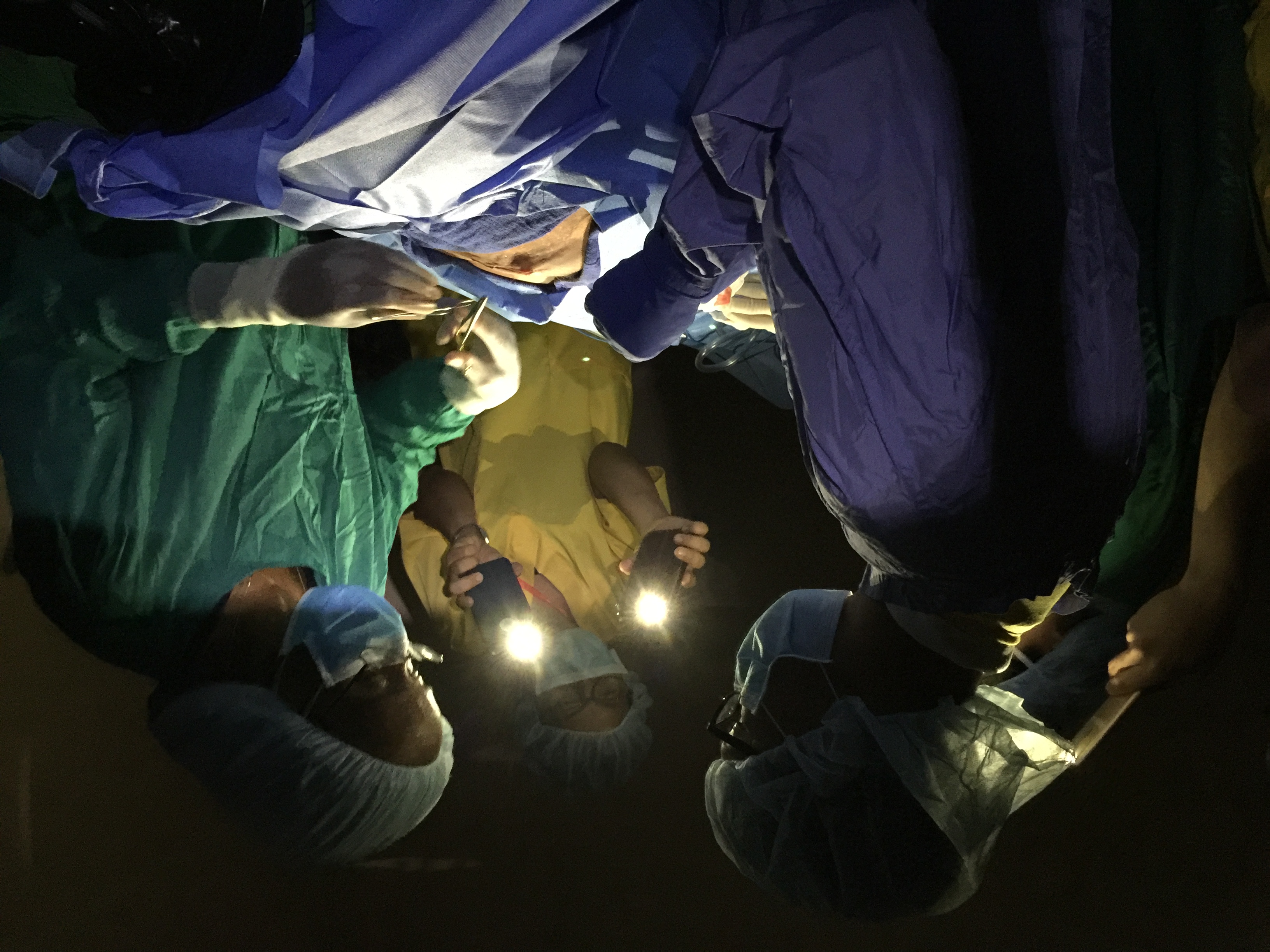

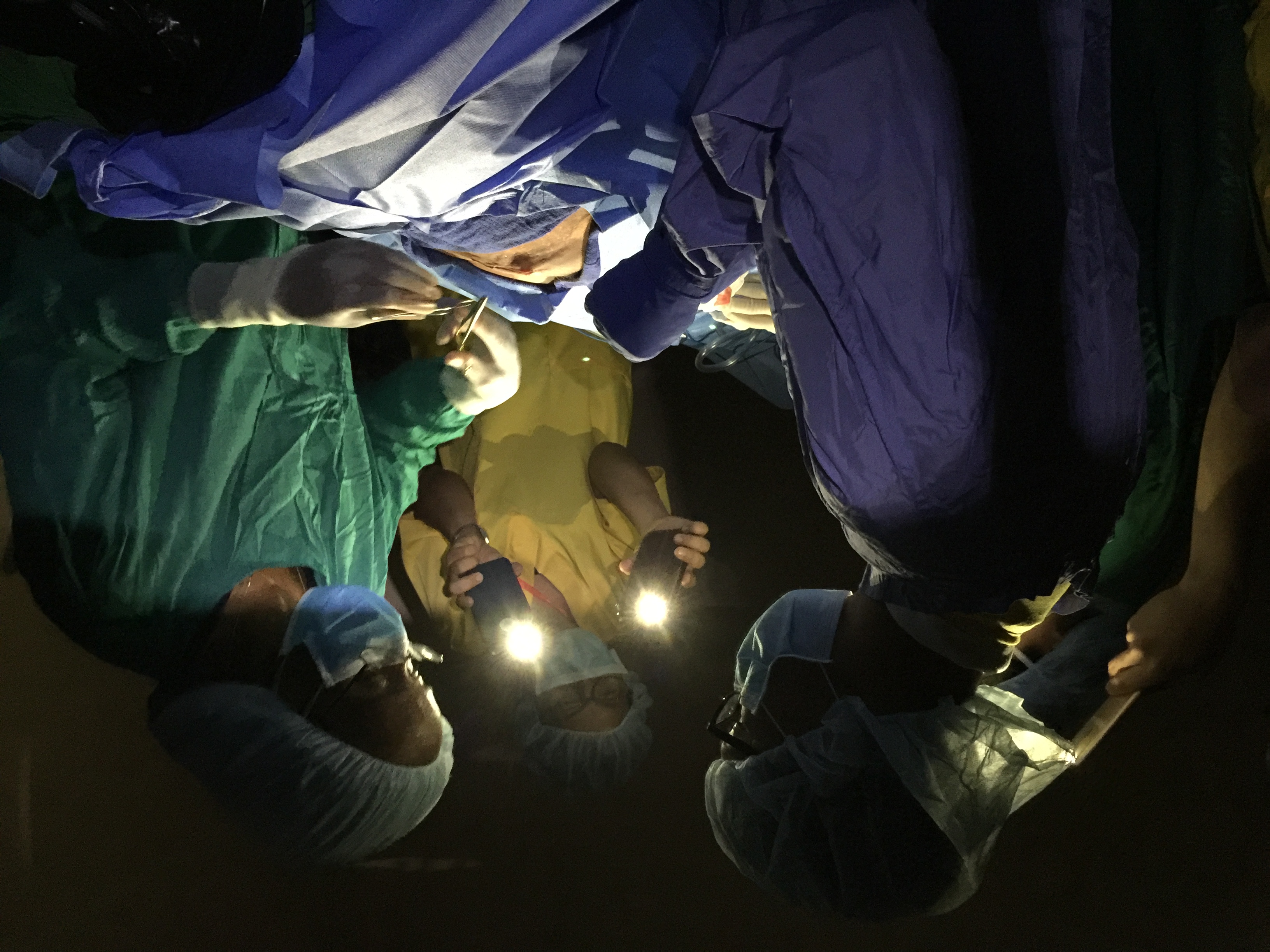

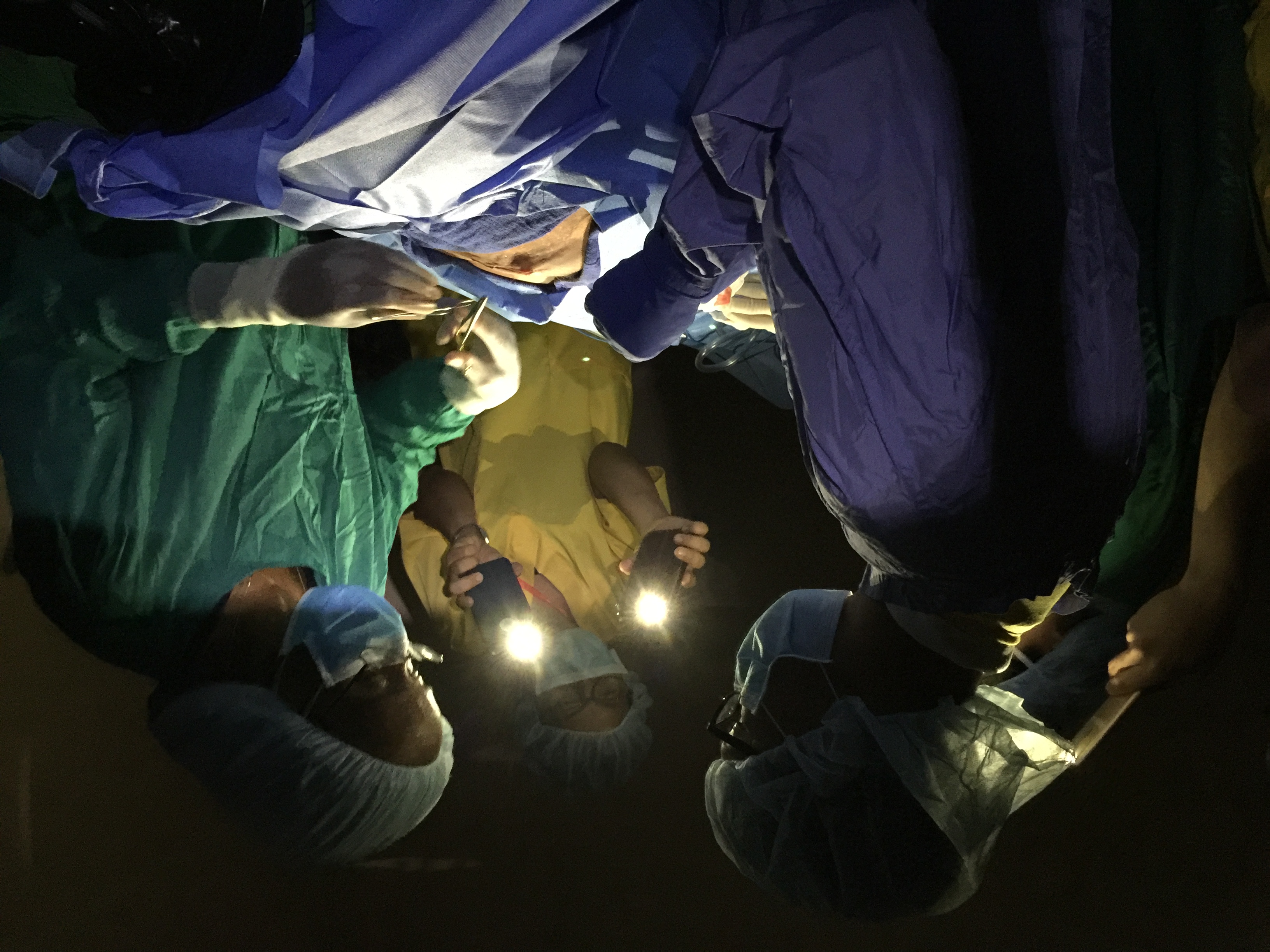

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits Power failures are common in rural Cambodia. One that occurred during surgery required improvisation, with several mobile phones providing light. Where Health Care Is a Luxury Power failures...