by dom-wp-admin | Feb 26, 2024 | 2016, Invest in Science & Research 2016

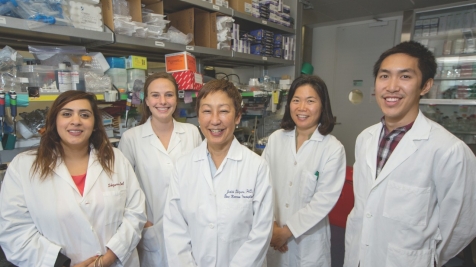

Baldeep Singh, MD, with staff at Samaritan House Making Bone Marrow Transplantation Safe Baldeep Singh, MD, with staff at Samaritan House Making Bone Marrow Transplantation Safe Bone marrow transplantation is so dangerous and so toxic that it is reserved for people...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2016, Invest in Science & Research 2016

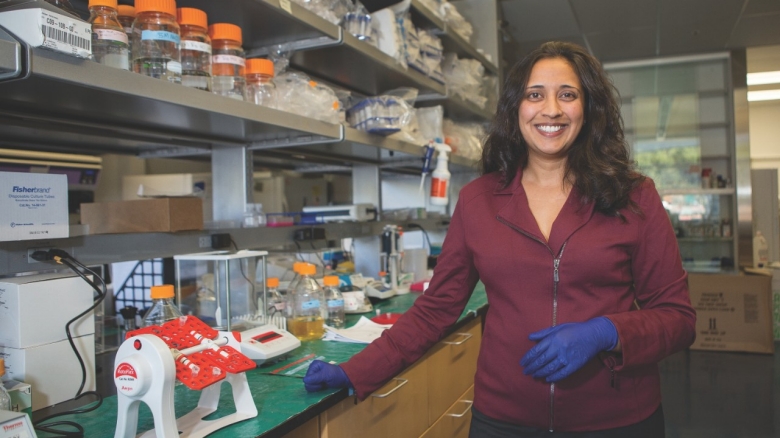

Ami Bhatt, MD, PhD The World Within Us Ami Bhatt, MD, PhD The World Within Us As a child, Ami Bhatt, MD, PhD (assistant professor, Hematology, and assistant professor, Genetics), found herself drawn to science. “I was always curious, and I wanted to apply my curiosity...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2016, Invest in Science & Research 2016

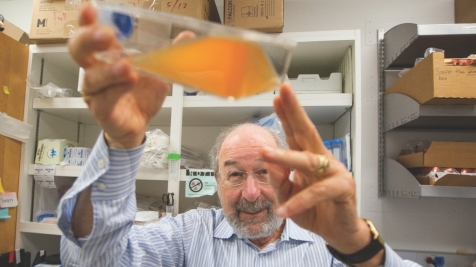

Ronald Levy, MD, today (top) and in 1981 (below) Drug Synergy May Upend Cancer Treatment Ronald Levy, MD, today (top) and in 1981 (below) Drug Synergy May Upend Cancer Treatment For decades, scientists have diligently been working toward new treatments for cancers by...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2016, Invest in Science & Research 2016

John Ioannidis, MD, DSc Applying the Science of Health and Wellbeing John Ioannidis, MD, DSc Applying the Science of Health and Wellbeing To date, wellness has been difficult to define scientifically because it encompasses all the delicate and exciting experiences...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2016, Invest in Science & Research 2016

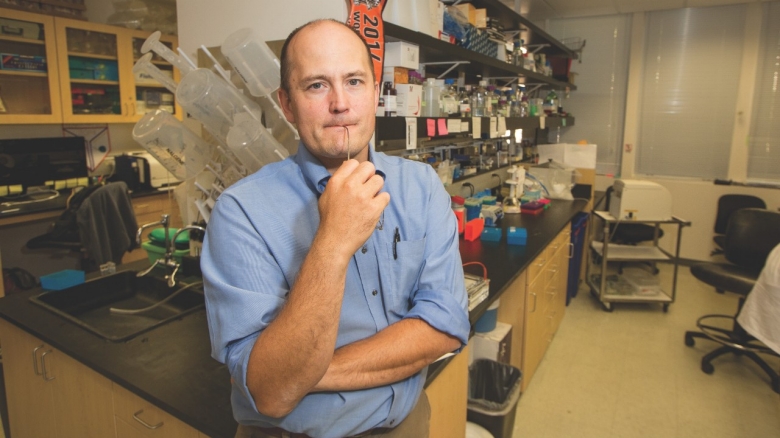

Paul Bollyky, MD New Plays to Tackle Inflammation and Infection Paul Bollyky, MD New Plays to Tackle Inflammation and Infection It’s a natural—and usually beneficial—response of the human body to react to a wound or pathogens with angry, red swelling. A sore knee or...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2016, Invest in Science & Research 2016

Lee Sanders, MD, and Marcella Alsan, MD, PhD, MPH How a Pesky Parasite Impacts Africa Lee Sanders, MD, and Marcella Alsan, MD, PhD, MPH How a Pesky Parasite Impacts Africa Stanford Assistant Professor of Medicine Marcella Alsan had always wondered why the mineral-rich...