by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2017, at home 2017

Sun Kim, MD, stands ready to help as Alan Pao, MD, cooks family dinner at home in Palo Alto. The Lives and Times of Two-Doctor Families Sun Kim, MD, stands ready to help as Alan Pao, MD, cooks family dinner at home in Palo Alto. The Lives and Times of Two-Doctor...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2017, at home 2017

Julie Parsonnet, MD, is a resident fellow in Robinson House. Here, she is seen walking with Todor Markov (left) and Scott Lambert, two Robinson House undergraduates. A Research Career to Benefit Children and a Life Lived on Campus Among Undergraduates Julie Parsonnet,...

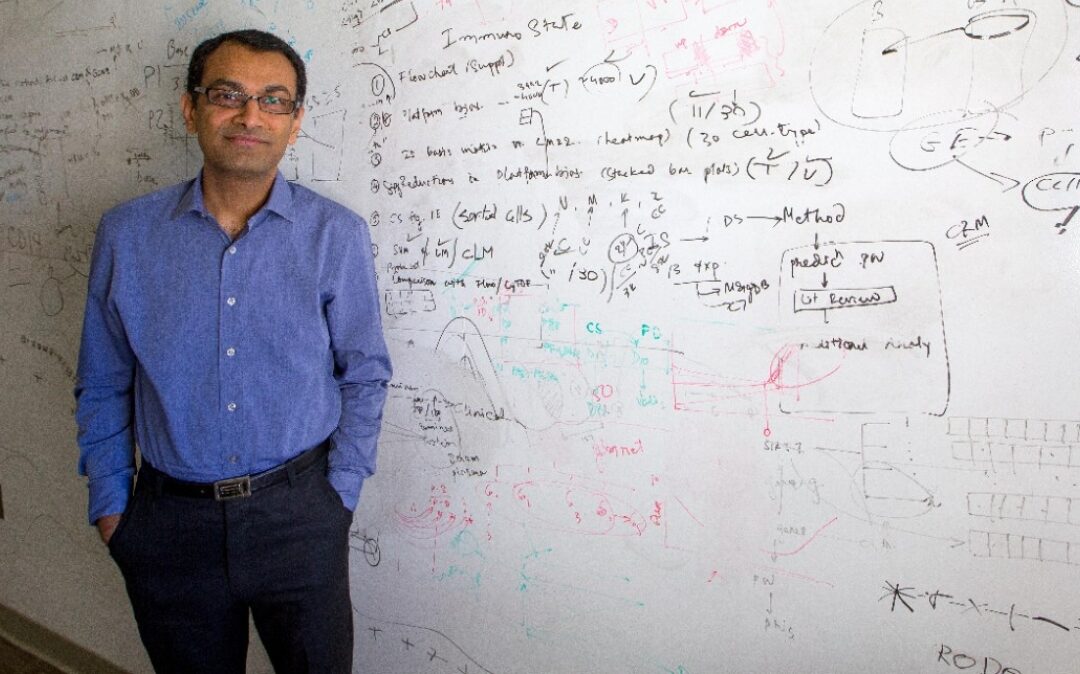

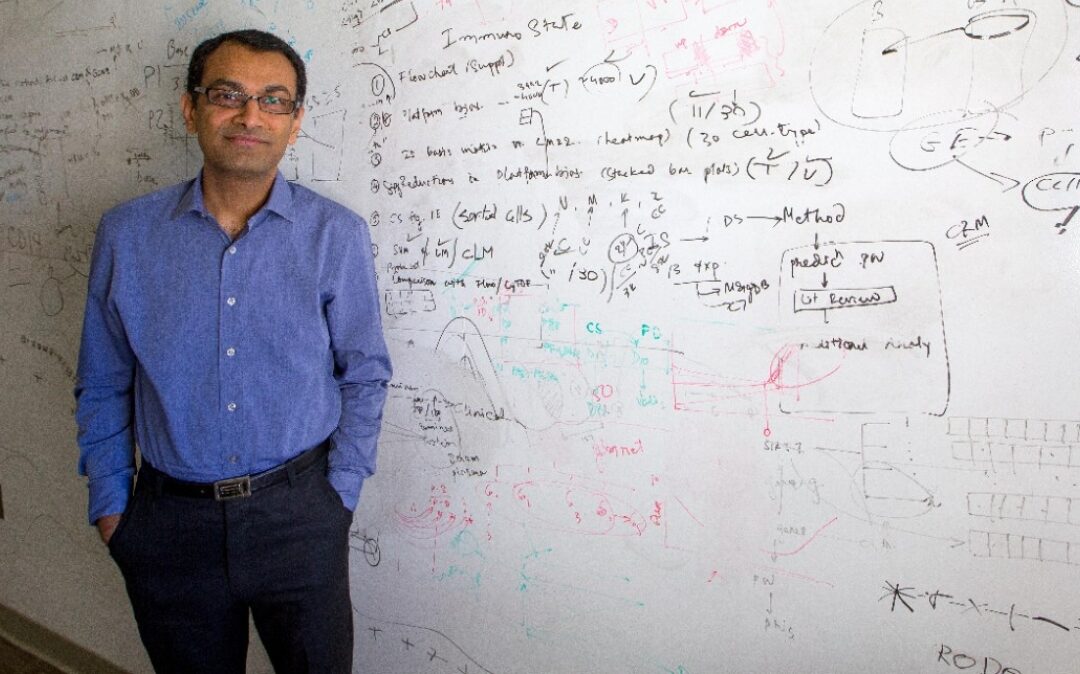

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2017, in research 2017

Purvesh Khatri, PhD Adventures of a Proud Data Parasite Purvesh Khatri, PhD Adventures of a Proud Data Parasite In an era in which analyzing other people’s data has been likened to research parasitism by no less an authority than The New England Journal of...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2017, in research 2017

Crystal Mackall, MD Riding the Immunotherapy Wave of the Future Crystal Mackall, MD Riding the Immunotherapy Wave of the Future Today, most pills dispensed to patients — whether for diabetes, cancer or another disease — are made of synthetic proteins or other lifeless...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2017, in research 2017

Walter Park, MD Sometimes Diabetes Means Cancer Walter Park, MD Sometimes Diabetes Means Cancer Walter Park, MD, an assistant professor of gastroenterology & hepatology, acknowledges that it will be many years before he recognizes the fruits of two of his current...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2017, in research 2017

Lauren Cheung, MD, MBA, Mintu Turakhia, MD, Sumbul Desai, MD The Center for Digital Health Is Open for Business Lauren Cheung, MD, MBA, Mintu Turakhia, MD, Sumbul Desai, MD The Center for Digital Health Is Open for Business Recent conversations with architects of the...