by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2019, caring for our patients 2019

Current Walk with Me partners: patient VANESSA DEEN JOHNSON (left) and medical student CLAIRE RHEE. Walk with Me: Early Clinical Experiences for Medical Students Current Walk with Me partners: patient VANESSA DEEN JOHNSON (left) and medical student CLAIRE RHEE. Walk...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2019, caring for our patients 2019

Lay health worker GEE ZHU (center) and MANALI PATEL, MD (right) meet with patient DONALD FREDERICK Delivering Care by Taking a Step Back Lay health worker GEE ZHU (center) and MANALI PATEL, MD (right) meet with patient DONALD FREDERICK Delivering Care by Taking a Step...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2019, caring for our patients 2019

KATE LUENPRAKANSIT, MD Putting Bioethics into Practice KATE LUENPRAKANSIT, MD Putting Bioethics into Practice Bioethics is a rapidly evolving, more-relevant-every-day kind of field. And for Kate Luenprakansit, MD, clinical assistant professor of hospital medicine and...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2019, caring for our patients 2019

ORNELIA WEYAND, MD Stanford Vasculitis Clinic: Infrequently Asked Questions about Uncommon Diseases ORNELIA WEYAND, MD Stanford Vasculitis Clinic: Infrequently Asked Questions about Uncommon Diseases Vasculitis, a group of uncommon diseases characterized by...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2019, caring for our patients 2019

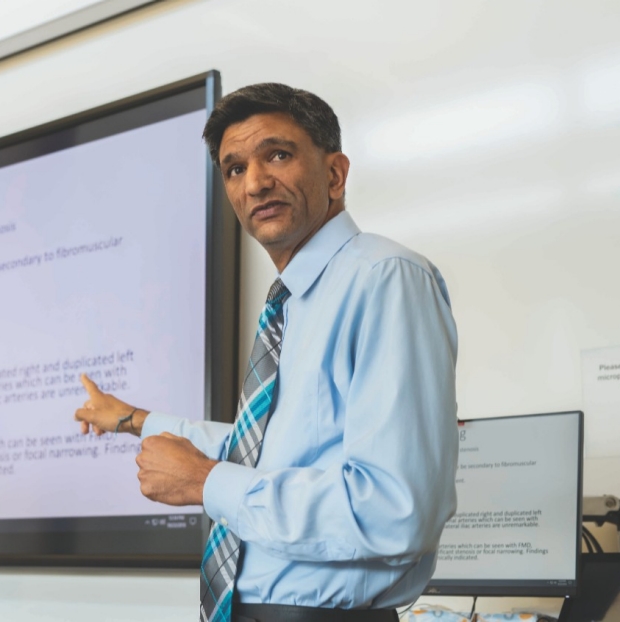

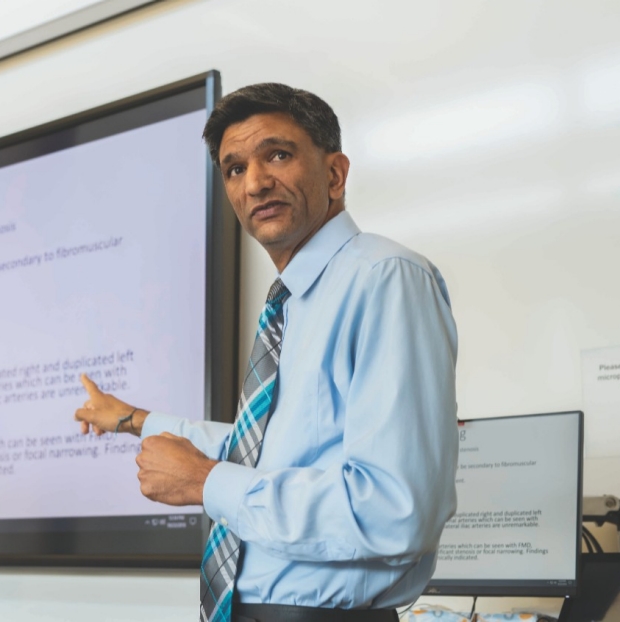

VIVEK BHALLA, MD Tackling a Fundamental Disease: Multiple Disciplines Take on Hypertension VIVEK BHALLA, MD Tackling a Fundamental Disease: Multiple Disciplines Take on Hypertension A multidisciplinary clinic at Stanford is redefining what it means to live with...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2019, caring for our patients 2019

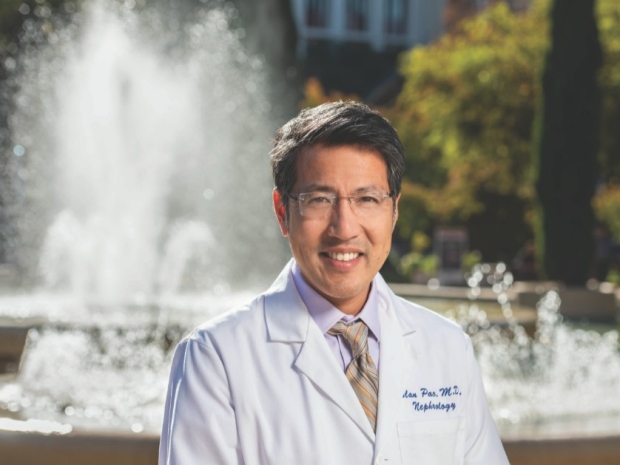

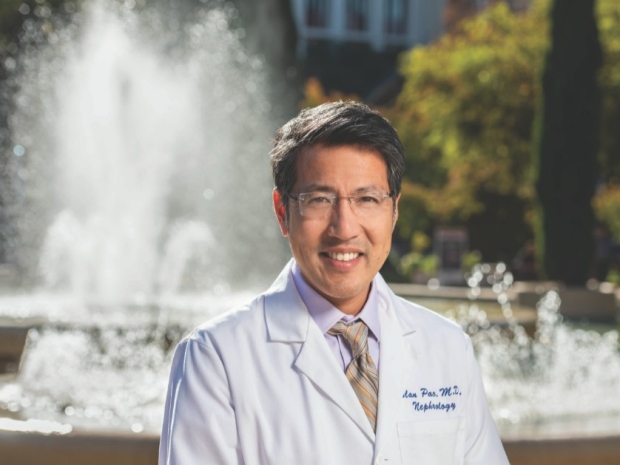

ALAN C. PAO, MD When It Comes to the Kidneys, This Center Leaves No Stone Unturned ALAN C. PAO, MD When It Comes to the Kidneys, This Center Leaves No Stone Unturned Half a million Americans go to the emergency room annually for kidney stone issues, and one in every...