by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2022, global and local challenges 2022

Patients Find Peace and Answers at Stanford’s Long Covid Clinic Hector Bonilla, MD (left) and Linda Geng, MD, PhD Hector Bonilla, MD (left) and Linda Geng, MD, PhD Patients Find Peace and Answers at Stanford’s Long Covid Clinic As symptoms persisted,...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2022, global and local challenges 2022

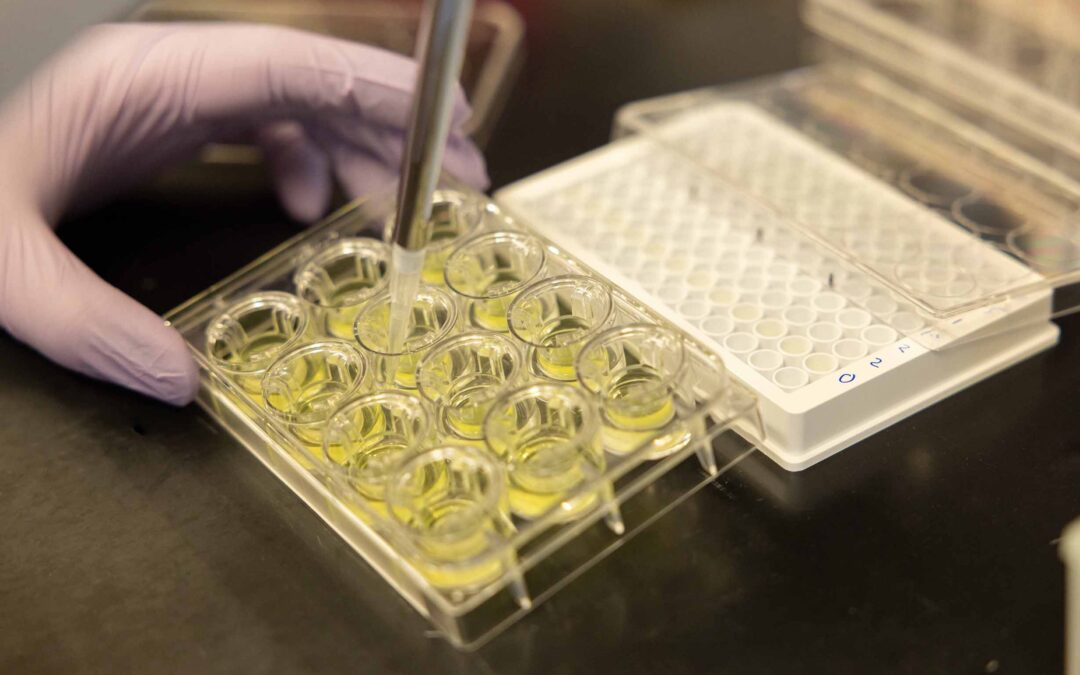

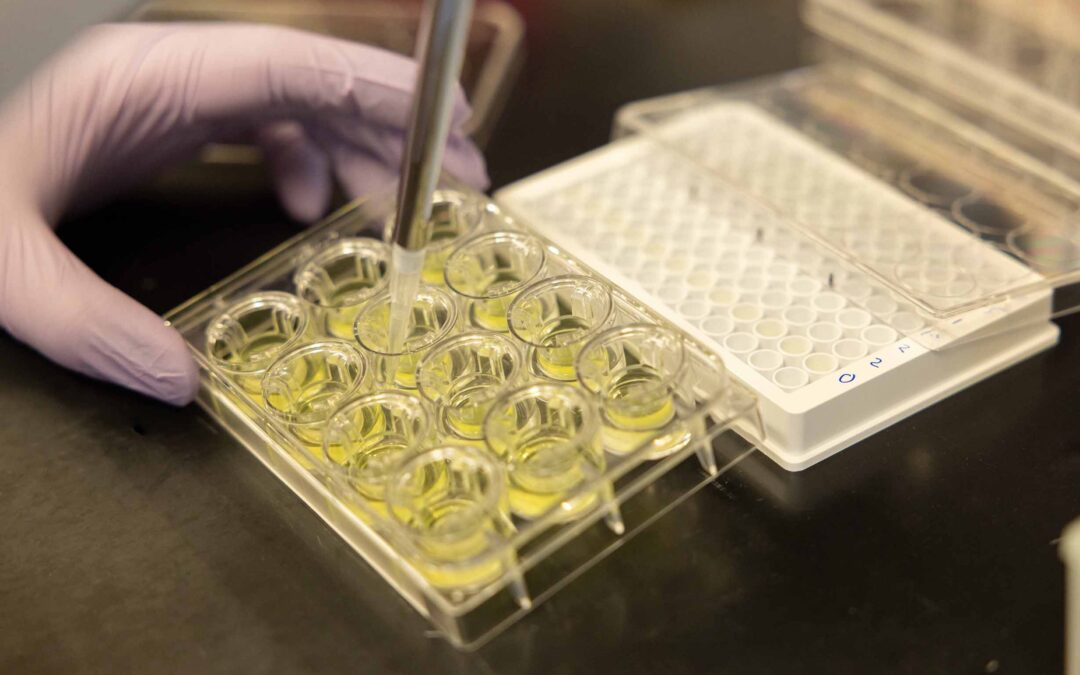

Developing Antivirals for COVID-19 and Beyond Stanford Researchers Design Novel Therapies to Prevent Drug Resistance Developing Antivirals for COVID-19 and Beyond Stanford Researchers Design Novel Therapies to Prevent Drug Resistance Almost every day, news outlets...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2022, global and local challenges 2022

Turning Climate Despair into Action Generation Dread Confronting Climate Change’s Toll on Mental Health Britt Wray, PhD Britt Wray, PhD Turning Climate Despair into Action Generation Dread Confronting Climate Change’s Toll on Mental Health In her new book Generation...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2022, global and local challenges 2022

Smoothing the Pathway Home for Older Patients Smoothing the Pathway Home for Older Patients As part of her training in geriatric medicine, Marina Martin, MD, MPH, spent time in assisted living facilities and visited patients at home. She knew that after a hospital...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2022, global and local challenges 2022

Surge Teams to the Rescue Surge Teams to the Rescue An influx of patients both during and after pandemic waves forced physicians and administrators to get creative and provide optimal care. Even though the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a pandemic in March 2020, the...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2022, global and local challenges 2022

Open Science at Stanford Promoting Data Access, Credibility, and Reproducibility For All Open Science at Stanford Promoting Data Access, Credibility, and Reproducibility For All Ten years ago, Amgen, a biotech company in Los Angeles, tried to replicate what it...