by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2021, all stories 2021

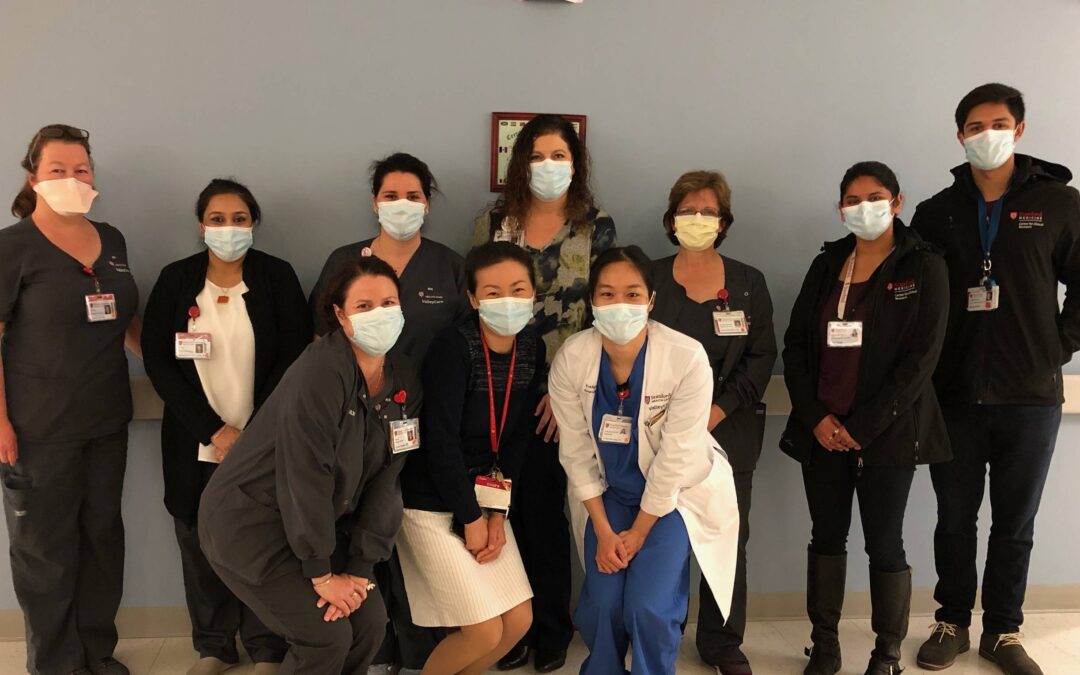

Caring for COVID-19 Patients:Department of Medicine ComesTogether to Serve CommunityImpacted by COVID-19 From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, through two surges, and now during a “new normal,” one thing has never changed: The Stanford Department of Medicine...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2021, all stories 2021

A Dedicated Clinic for COVID-19 Patients How Stanford’s CROWN Clinic provides support after a COVID-19 diagnosis A Dedicated Clinic for COVID-19 Patients How Stanford’s CROWN Clinic provides support after a COVID-19 diagnosis Linda Barman, MD, associate director of...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2021, all stories 2021

Stanford Lends a Hand ————————– From grocery runs to online fundraisers, the Department of Medicine community found ways to help others amid the coronavirus pandemic Stanford Lends a Hand...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2021, all stories 2021

A COVID Trial Pitches a Tent in the Great Outdoors When you think of advanced clinical trials, you usually don’t think of a tent. But that’s where you’d be wrong—in April 2020, when COVID felt new and every breath was terrifying, a tent was just what the doctor...

by emli1120 | Feb 26, 2024 | 2021, all stories 2021

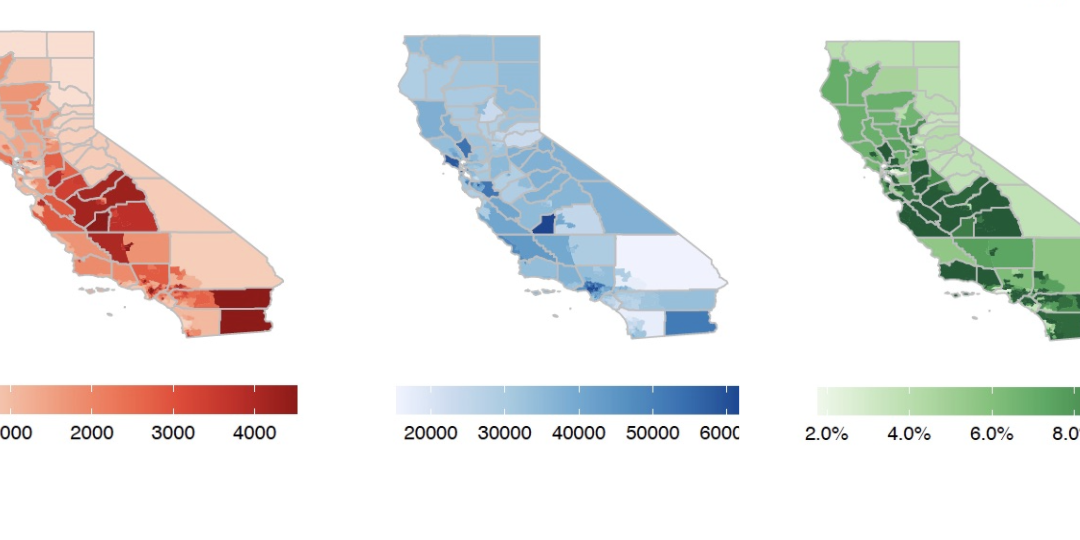

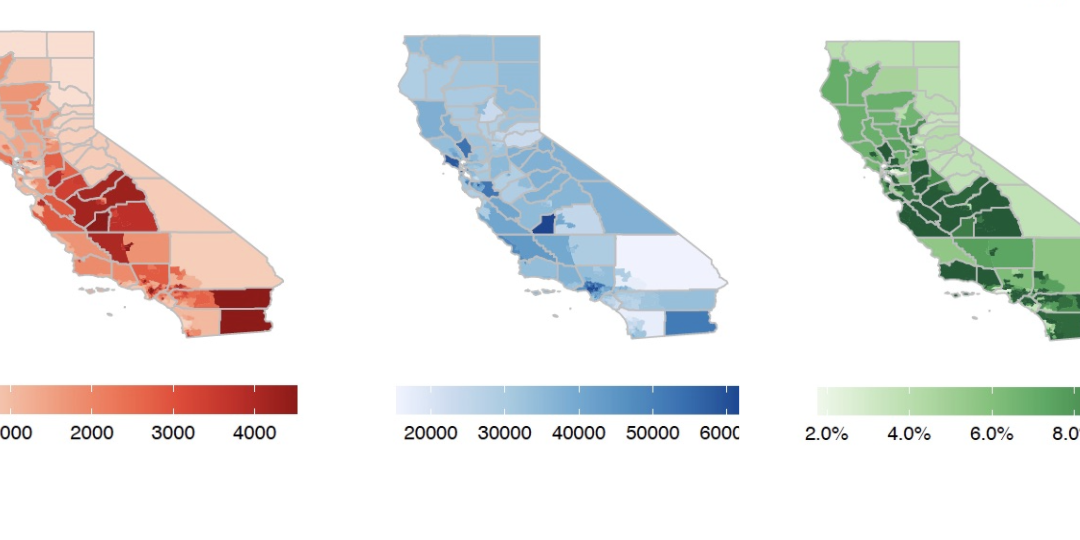

COVID-19 Modeling Team at Forefront of Pandemic Projections and Planning COVID-19 Modeling Team at Forefront of Pandemic Projections and Planning Just weeks after the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a global pandemic in March 2020, a team of...