by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Clinical Care 2023

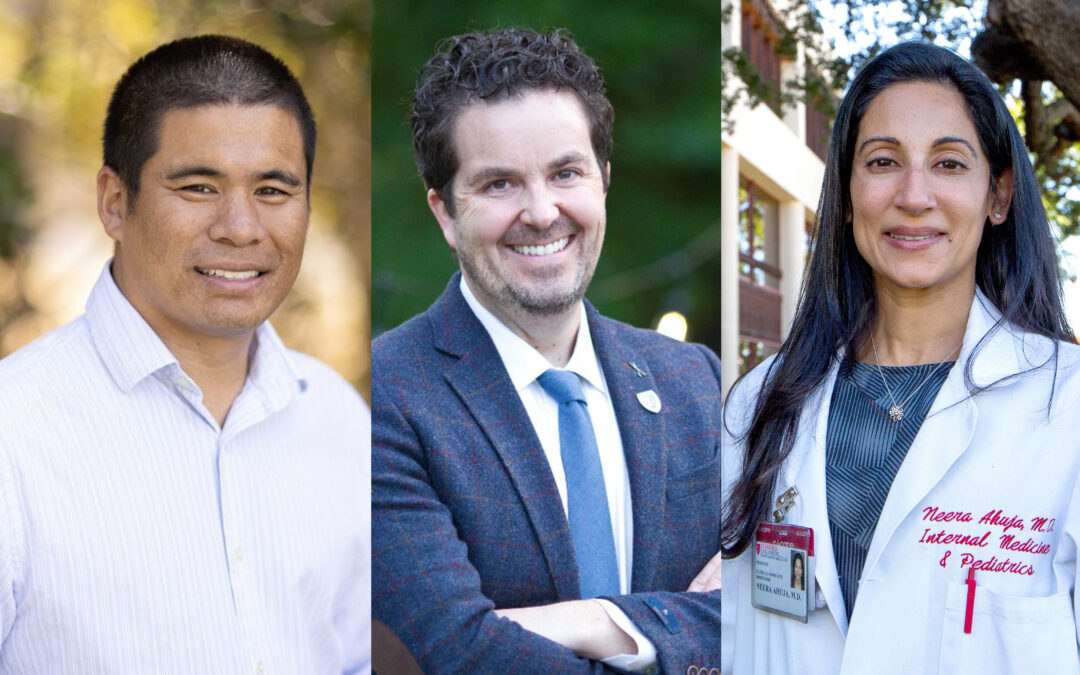

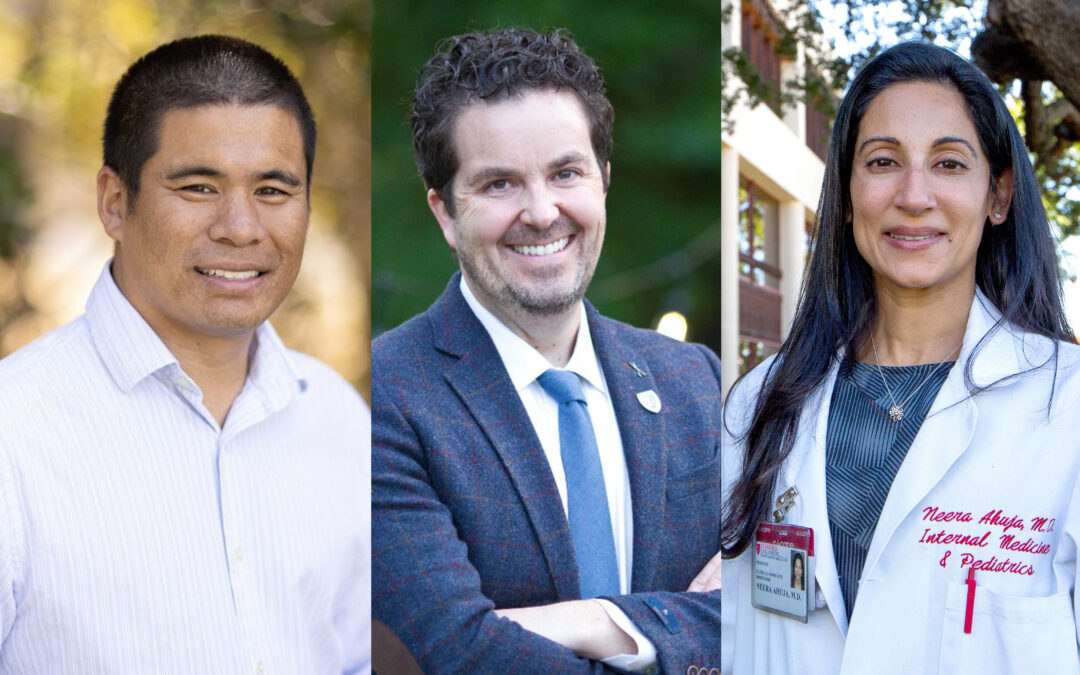

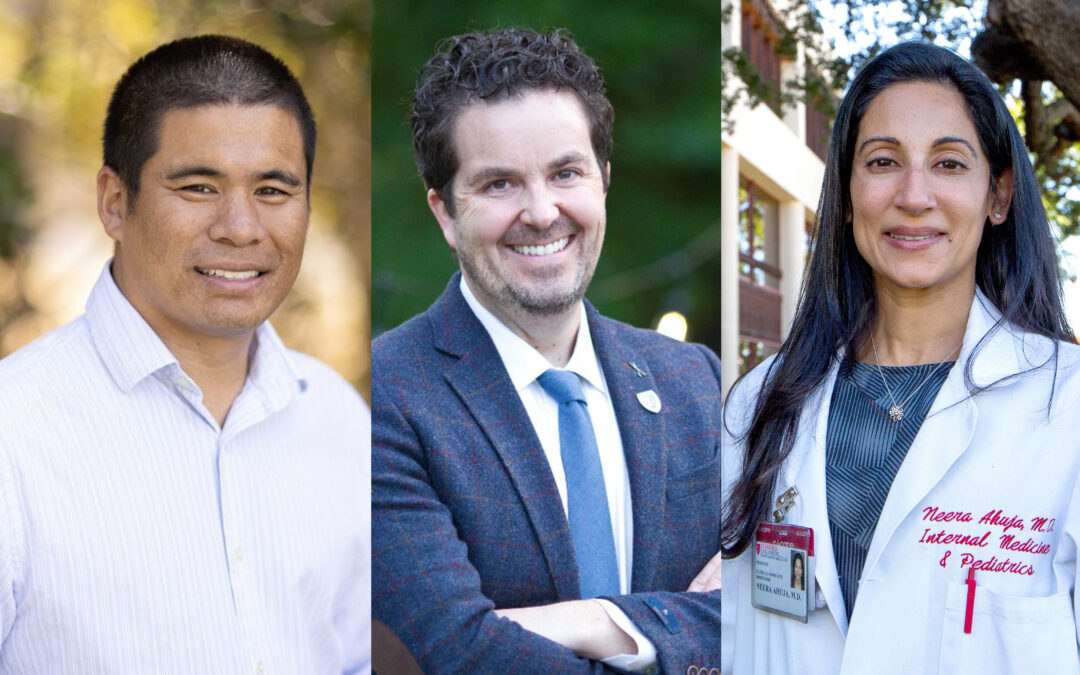

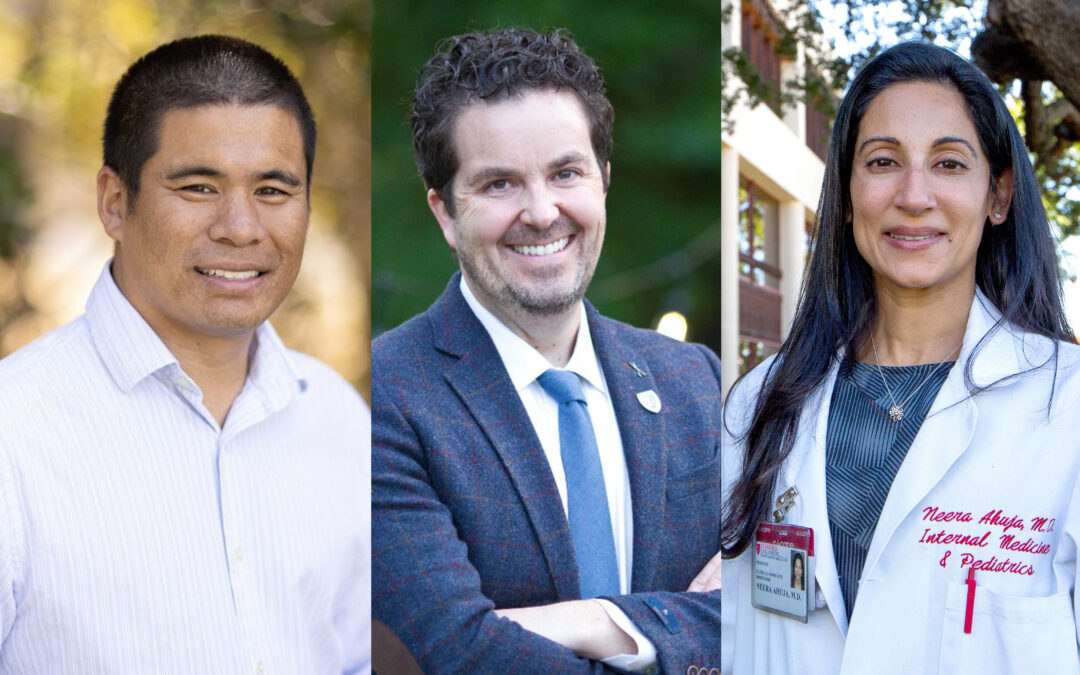

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits From left: Jeffrey Chi, MD; Tyler Johnson, MD; Neera Ahuja, MD Hospital Medicine and Oncology Rise to Meet the Needs of More Patients From left: Jeffrey Chi, MD; Tyler Johnson, MD; Neera...

by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Clinical Care 2023

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits The Clinical Informatics Group uses AI to improve how doctors and nurses identify and assess hospitalized patients at risk of deterioration. Clinical Informatics Harnesses Information...