by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Research 2023

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits Renewing the Field Nurturing the Next Generation of Infectious Disease Physician-Scientists Renewing the Field Nurturing the Next Generation of Infectious Disease Physician-Scientists The...

by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Research 2023

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits Mary Varkey, clinical research coordinator, with a RECOVER participant. SCCR’s Quality and Compliance Team Shows Resilience Amid Pandemic Pivots Mary Varkey, clinical research coordinator,...

by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Research 2023

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits Susan S. Jacobs, MS, RN Driving Medical Progress Susan Jacobs’ 25-Year Journey in Clinical Research Leadership Susan S. Jacobs, MS, RN Driving Medical Progress Susan Jacobs’ 25-Year Journey...

by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Research 2023

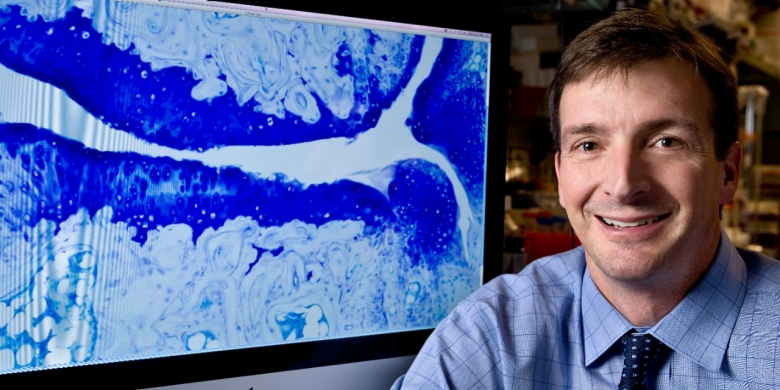

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits Everett Meyer, MD, PhD Teaching Tolerance to the Immune System A Q&A with Everett Meyer Everett Meyer, MD, PhD Teaching Tolerance to the Immune System A Q&A with Everett Meyer A...

by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Research 2023

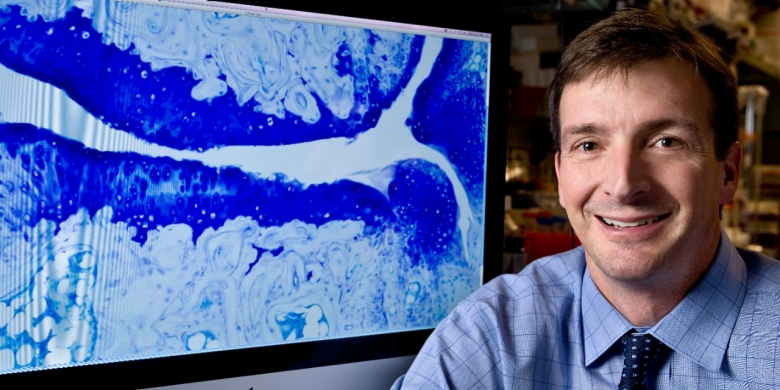

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits William Robinson, MD, PhD Revealing Microbial Triggers of Autoimmune Disease William Robinson, MD, PhD Revealing Microbial Triggers of Autoimmune Disease For decades, scientists have...

by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Research 2023

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits From left: Cailin Collins, MD, Peter Greenberg, MD, and Gabe Mannis, MD On the Hunt for Knowledge Two Hematologists, Two Challenging Diseases, Two Careers Dedicated to the Pursuit of Answers...