by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Rebuilding Community Connections 2023

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits Baldeep Singh, MD, with staff at Samaritan House Rethinking Care and Community in Community-Based Care Baldeep Singh, MD, with staff at Samaritan House Rethinking Care and Community in...

by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Rebuilding Community Connections 2023

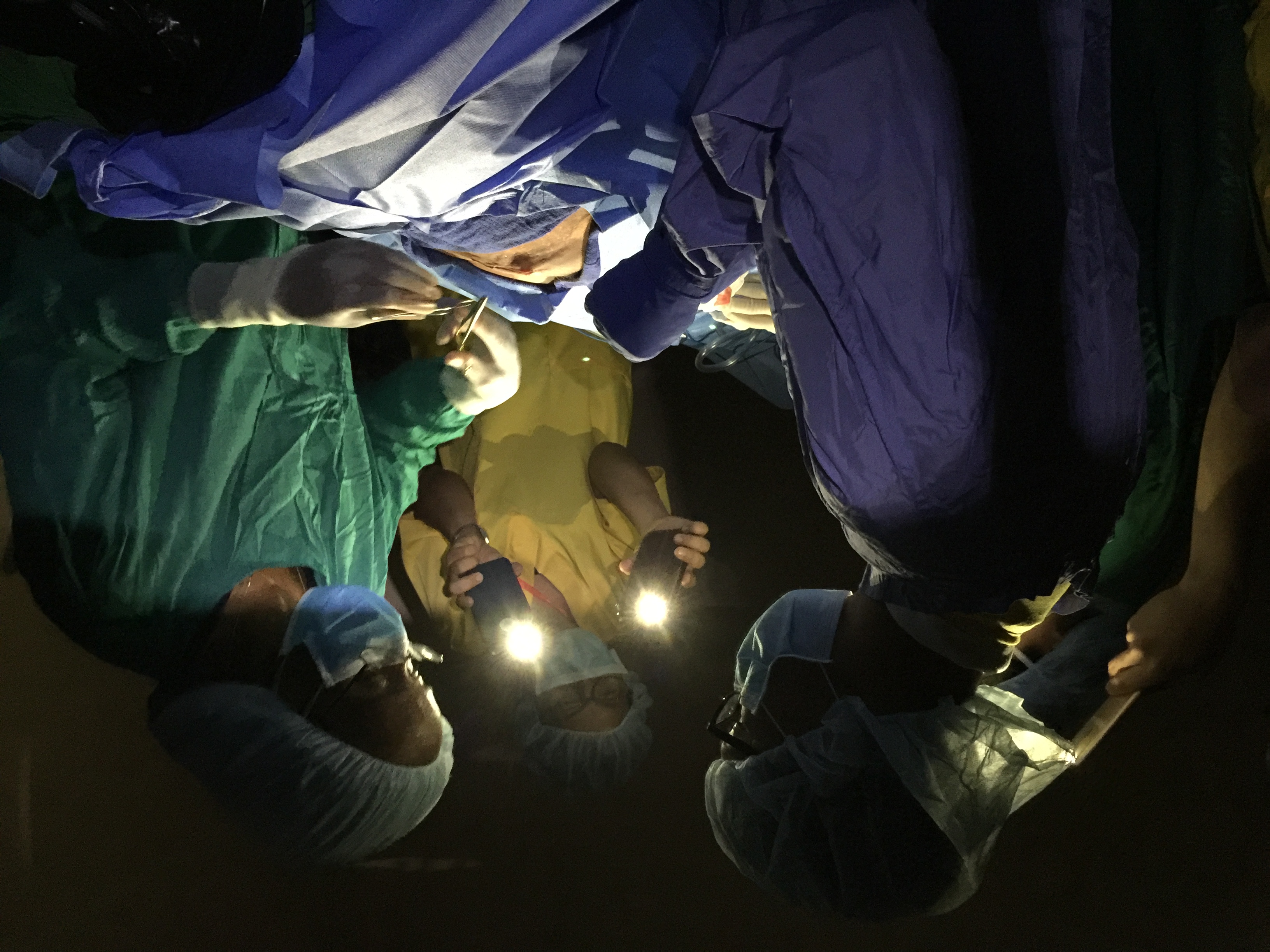

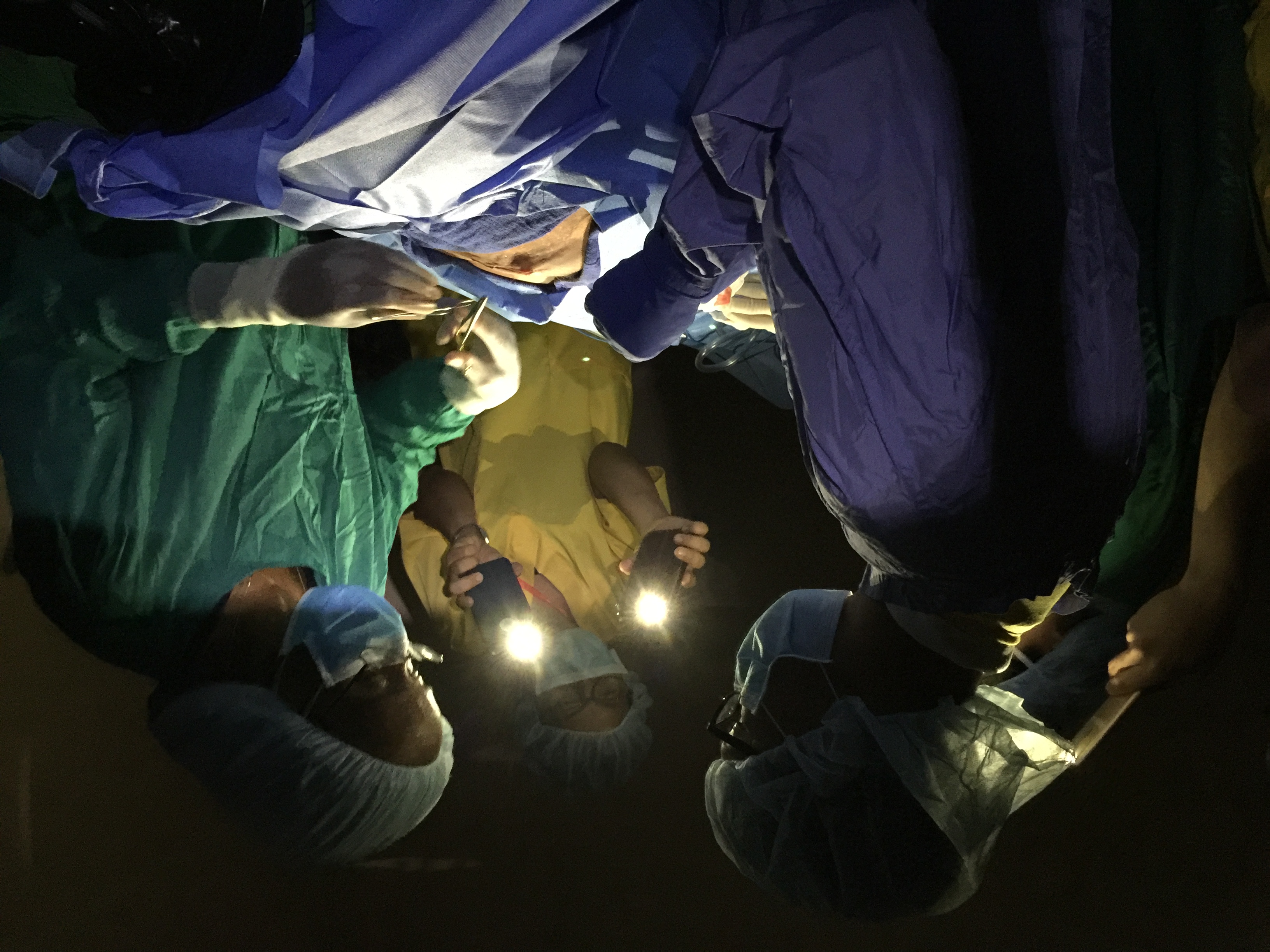

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits Power failures are common in rural Cambodia. One that occurred during surgery required improvisation, with several mobile phones providing light. Where Health Care Is a Luxury Power failures...

by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Clinical Care 2023

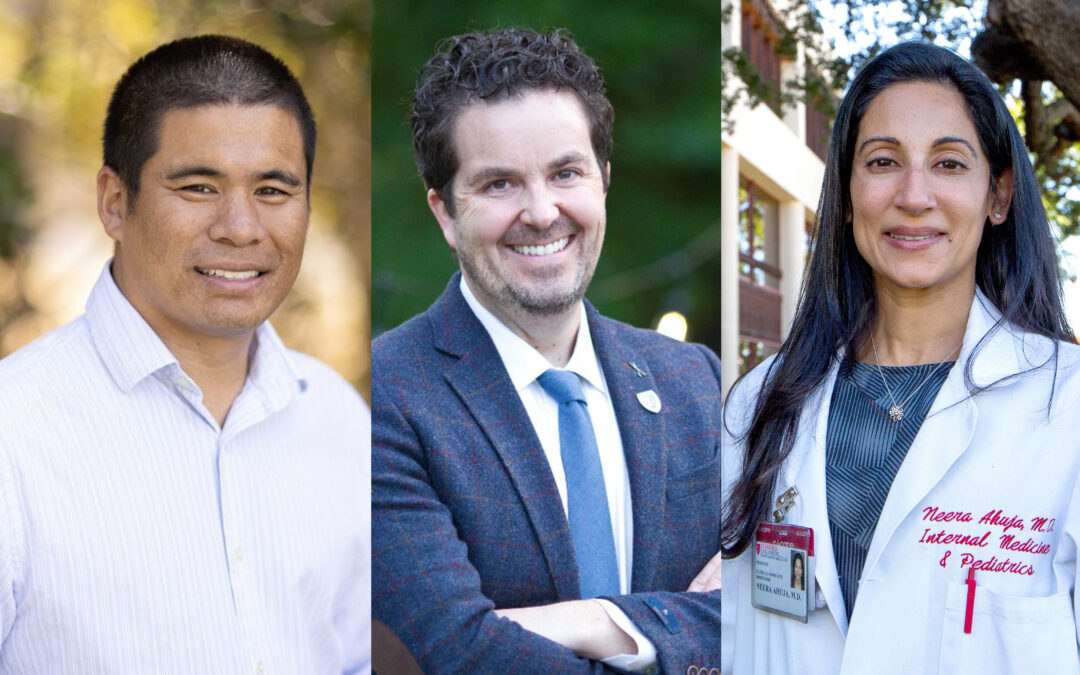

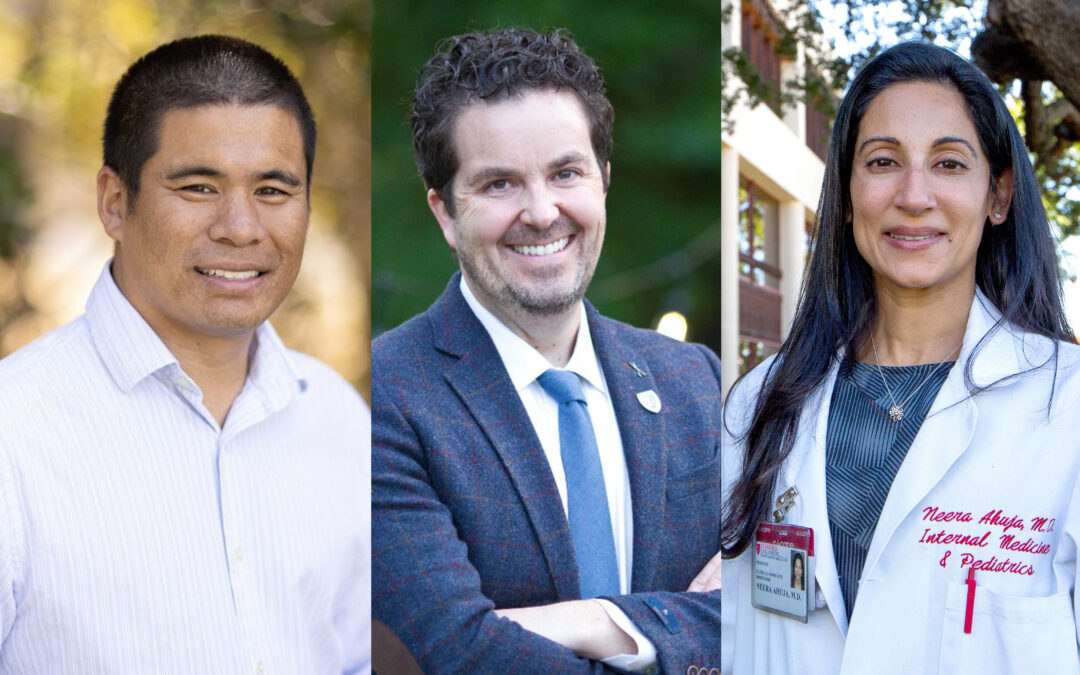

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits From left: Jeffrey Chi, MD; Tyler Johnson, MD; Neera Ahuja, MD Hospital Medicine and Oncology Rise to Meet the Needs of More Patients From left: Jeffrey Chi, MD; Tyler Johnson, MD; Neera...

by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Clinical Care 2023

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits The Clinical Informatics Group uses AI to improve how doctors and nurses identify and assess hospitalized patients at risk of deterioration. Clinical Informatics Harnesses Information...

by dom-wp-admin | Feb 27, 2024 | 2023, Research 2023

2023 Annual Report Welcome Department by the Numbers All 2023 Stories Credits From left: Cailin Collins, MD, Peter Greenberg, MD, and Gabe Mannis, MD On the Hunt for Knowledge Two Hematologists, Two Challenging Diseases, Two Careers Dedicated to the Pursuit of Answers...